by Marie Cohen

Recognizing implicit bias in mandated reporting training is a national focus for addressing racial inequity in child welfare. States from New York to Washington have updated their training for mandatory reporters to include implicit bias or highlight the distinction between neglect and poverty in an effort to reduce racial disparities in child welfare involvement. My recent experience taking the updated training in Washington DC made clear that there is a fundamental conflict between preparing mandated reporters for their responsibility to report and advising them to assess their biases before reporting. The basic conflict is this: the core training instructs mandatory reporters to report any suspicion of abuse or neglect, while the implicit bias unit urges mandatory reporters to doubt their instincts and reconsider their duty to report.

In FY 2023, the District of Columbia’s Child and Family Services Agency (CFSA) updated its online mandated reporter training to include a module focused on understanding and addressing implicit bias for mandated reporters. This training is required for all mandated reporters, who include both professionals (doctors, nurses, teachers, social workers, etc.) and volunteers who work with children. I had taken the training several times in the past–first for my work as a social worker with CFSA and later as a mentor to a foster youth. I had my first experience with the updated training last month as part of my preparation to serve as a Court Appointed Special Advocate (CASA) for a child in foster care.

The Implicit Bias Module

The implicit bias module appears to have been shoehorned into the existing DC mandatory reporter training right after a brief introduction to mandatory reporters and their role. The video introducing the section explains that implicit bias harms “families of color” in the child welfare system, without providing any evidence of such harm. It goes on to assert that “the point of this portion of the training is to make sure that reporting is based on observations and not assumptions. Ultimately we want mandated reporters to consider this before responding to a child’s disclosure of suspected abuse or neglect: Do I have any implicit bias in my decision to call or not to call the hotline.” It may sound reasonable, but as the training unfolds, a conflict with the goals of the overall training and mandatory reporting itself becomes clear.

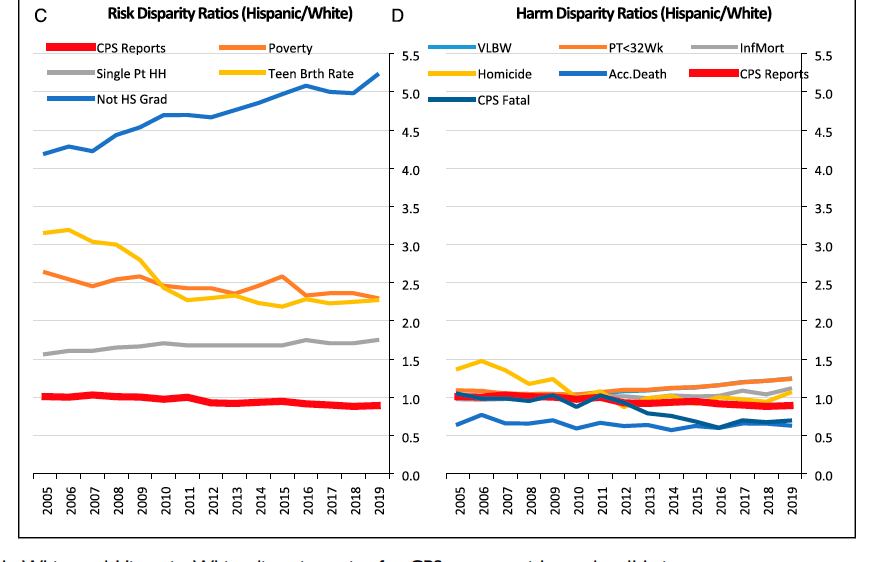

The implicit bias module continues by explaining that nationally and in DC, mandated reporters call the CFSA hotline about Black families disproportionately more than White families; this leads to more “Black and Brown” children having in-home cases or entering foster care because they are assessed more closely. A graph has been provided, with text saying “In this graph, disproportionality is where you see that Black and Brown children make up approximately 64% of hotline calls. However, only 57% of people in the District are a race/ethnicity other than white.” Unfortunately, one does not see this in the graph, which does not include hotline calls at all! It does include children who are the subject of an investigation after a call to the CFSA hotline, and it shows that Black children made up 57 percent of the investigated children, while comprising 53 percent of the population. That is a very small disparity, and in any case could reflect unequal rates of abuse and neglect between Black and White children. The data does show a larger Black-White disparity in confirmed maltreatment (71 percent of the children confirmed as maltreated are Black) and “foster care” (whether this is children in care or entries into care is unclear) at 92 percent. But these increasing disparities come in at the investigation stage (where the substantiation and foster care decisions are made), not at the reporting stage, calling into question the need for training mandatory reporters about implicit bias. To make matters worse, the data on investigations contain a whopping 40 percent without race or ethnicity data; 26 percent of the confirmed maltreatment data, and 23 percent of the in-home case data also lack race and ethnicity information. (Note that the bars of the graph have been shifted by one column to the left of the corresponding columns from the numerical table, as in the original.) So it is impossible to draw meaningful conclusions from these data.

Other than the mention of the hotline call data, which is missing from the graph, the only analysis of the data in the text reads as follows. “Disparity occurs when these children and families have cases open to either in home or foster care support. As you can see that [sic] 85% of in-home cases, and more than 92% of foster care cases in 2020 were opened with Black and brown families, while again the District’s make-up is only 57% Black and brown.” The inclusion of “brown families” is somewhat disingenuous. The graph shows that Hispanics and Asians, the only “brown” children with non-zero populations on the graph, are underrepresented in investigations, confirmed maltreatment, foster care, etc.1 Switching categories, the lecturer goes on to state that “At every stage, Black and Indigenous families face racial discrimination and unequal treatment.” DC is not known to have a large indigenous population; there is no row on the table for Native Americans, and Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders are zero percent of every category except that they are listed as making up two percent of children aging out of foster care in 2019.

A central motif of the training is that the confusion of poverty with neglect contributes to the racial and ethnic disparities in child welfare. The video states that “under current law, most children in the US are separated for neglect, a code word that typically represents conditions of poverty, resulting in disproportionate separation and harm to Black families….” But there is a problem with this. We know that neglect is often associated with serious drug abuse and/or mental illness. After all, most poor people don’t neglect their children. Moreover DC Code Section 16.2301 forbids a court to find maltreatment when the deprivation of food, clothing, shelter or medical care is due to the parent’s lack of financial means. The law does not allow removing children because of poverty in DC, and the small number of removals compared to investigations in DC (224 children placed in foster care compared to 3,767 investigations in FY 2024) suggests that CFSA does not remove children for poverty alone.

The training includes practice scenarios to help trainees distinguish between poverty (or “need” according to the training) and neglect. The participant must read the scenarios and decide whether they represent need (and presumably do not call for a hotline report) or neglect. After providing their own answer, trainees learn the “right answer” according to CFSA. One of the three “need” scenarios is particularly troubling and is reproduced here:

The 4-year-old child came into the center smelling of a strong smell and her nails are long and dirty. There is sticky stuff on her chest that is black underneath her shirt on her skin. The child often comes to the center unbathed. She was wearing shoes that were too small, but the dad was made aware, and he got her new shoes. The child comes in with an old pamper not changed, soaked or soiled. Sometimes she comes to school with the same clothes on from the day before or sometimes wears the same clothes for three days.

The child does not talk or engage with staff or peers. The mother has been observed yelling at the child and all she does is cry. The child covers her eyes but does not ask for anything.

The caller is aware that the family was recently evicted after the mother lost her full-time job and they are being supported on the income made from the father’s part-time employment. The family moves from the homes of family and friends because they refuse to go to a shelter. Caller suspects sometimes the family may sleep in the car.

The characterization of this scenario as “need” rather than neglect is troubling. The combination of factors that are cited suggest something more than poverty. The fact that the child “does not talk or engage with staff and peers,” and that the mother “has been observed yelling at the child and all she does is cry” suggest problems this beyond the realm of need. The refusal to go to a shelter under current conditions, when the District of Columbia guarantees shelter to families with children and has replaced its dilapidated shelter with modern new facilities, increases the likelihood that this is a case of neglect.

In the content that follows, a video tells mandatory reporters that although they are required by law to report suspected abuse or neglect, they should not make reports “solely based on assumptions, schemas, or biases.” It seems rather disrespectful to think that a doctor, nurse, teacher, social worker or volunteer would do this. Trainees are presented with the following questions to ask before making a report.

This is confusing indeed. Is the agency saying that mandatory reporters should not make a report “solely out of legal obligation,” even though they are legally required to report and could receive consequences for not doing so? Providing resources to assist the family is fine, but if there is abuse or neglect, does that exempt the reporter from the duty to report? It seems unlikely and unwise.

“Granted,” the presenter continues, “there are many times when you recognize your legal obligation, have the resources to support a family, and have checked your biases, and a report still needs to be made.” But the speaker goes on to state that “Each of us holds a responsibility to address disproportionality and disparity in the lives of Black and Brown families in the District.” She then invites us to “walk through how we can do this together,” by listening to two videos that are a total of five minutes in length. The first video, on “Mitigating Bias” counsels reporters to follow a three-step process consisting of of “deliberate,” “reflect,” and “educate,” with each step containing mutiple steps or suggestions. Mandatory reporters then learn about “cultural humility” and its three attributes: “lifelong learning and critical self-reflection,” “recognition and challenging of power imbalances,” and “institutional accountability.” And then training participants are told that “[u]ltimately, our goal is to ensure that children who are experiencing neglect in the District receive the support they need to thrive within their families. To do this effectively, we each have to ensure our implicit biases, whether personal or institutional, are not the foundation for calls to the CFSA hotline.” Apparently, no children in the District need to be removed from their families in order to thrive; even though the agency providing the training removed 244 children in the last Fiscal Year, as mentioned above.

To sum up, the implicit bias section of the training teaches child-serving professionals and volunteers that mandatory reporting harms Black children and that to avoid that harm, mandatory reporters must engage in a lengthy deliberative process before making a report. Mandatory reporters learn nothing of the costs of not making a report, which include the possible death of a child. They also learn nothing about the different risks facing Black children, who are three times more likely than White children to die of maltreatment.2 Instead, they are told that “we are delinquent in addressing the institutionalized racism and bias that pervades our family and wellbeing systems. This has been perpetuated by the misconception that we are nobly rescuing children from dangerous situations.” The clear implication is that making a report is much more risky than not making one.

A Case of Mixed Messages

After at least an hour of training on implicit bias, mandatory reporters finally arrive at the original training, which seems mainly unchanged. They learn about how to respond to a child’s disclosure of abuse or neglect. They learn they must report when they have reasonable cause to believe a child has been, or is in immediate danger of, being abused or neglected. They learn what and how to report. They learn that the identity of reporters is confidential and that failure to make a report can be punished by a fine of up to $1,000 or imprisonment for up to 180 days. They learn about different types of abuse and neglect, which children have higher risks of being maltreated, situations in which CFSA does not intervene, what happens when a report is made, and how child welfare services work in the District of Columbia. They are told to “[r]eport any suspicion of child abuse and neglect,” and that “every call matters!” A key instruction is buried in the section on how to distinguish discipline from child abuse. It says: “The good news is, as a mandated reporter, you do not need to know the details or all the facts before making a report. You just need to be suspicious of abuse/neglect and CFSA’s response, if it does respond, will do the rest.” (This should be moved to the top and emphasized, as it may have been in an earlier version of the training). In closing, trainees are told that:

Abuse and neglect place children at great risk of physical and emotional injuries and even death. As a mandated reporter, the District is expecting you to do the following:

- Recognize the signs of child abuse and neglect.

- When children have the courage to disclose abuse or neglect to you, take them seriously.

- When you suspect or know of incidents of child abuse or neglect, call CFSA at (202) 671-SAFE.

- Be responsible for calling the CFSA Hotline yourself, even if you have informed your supervisor.

- If necessary, be helpful and available during the investigation.

The fundamental conflict between the training’s two messages is clear. According to the original training, abuse and neglect are dangerous to children and it is our responsibility to report. According to the implicit bias section, it is reporting that is dangerous and needs to be inhibited. Neglect is a serious type of maltreatment according to the original training but a “code word”d according to the implicit bias section. It is not really surprising that the implicit bias element of the training seems to be in opposition to the preexisting content. Perhaps those who inserted this content would prefer to eliminate mandatory reporting training entirely and are just trying to minimize it within the requirements of current law. But the half-measure of trying to train the implicit bias out of mandatory reporters creates a training that simply does not make sense.

In addition to this fundamental disconnect, the training exhibits many factual errors and is padded with extraneous content. The factual errors are discussed in an addendum to this post. The extraneous content includes discussions of the racial wealth gap and instructions for “self-reflection, in which trainees are instructed to define their values by a three-step process that is painstakingly described in a three-minute video. Perhaps the most striking extraneous content is a section that describes in detail six types of “mental models related to diversity, equity and inclusion.” One of the six types is “active opposers,” who are typically deeply rooted in their choice to be a strong opponent of DEI. These are the people whose minds cannot be changed and who are committed to disrupting the work of DEI.” One cannot help wondering how the current federal leadership would respond if they knew of this content, and being offended at the disrespect for the time of busy professionals or volunteers.

In summary, there is a fundamental conflict between the original message of CFSA’s mandatory reporter training and the message of the implicit bias unit that has been added to it. Unlike the original message stressing the duty and importance of reporting suspected abuse and neglect, the new message states that reporting damages children and families of color and should be avoided whenever possible. This fundamental conflict is not unique to the District and by necessity affects all mandatory reporter trainings that attempts to temper the duty to report by inserting considerations related to race and ethnicity.

Notes

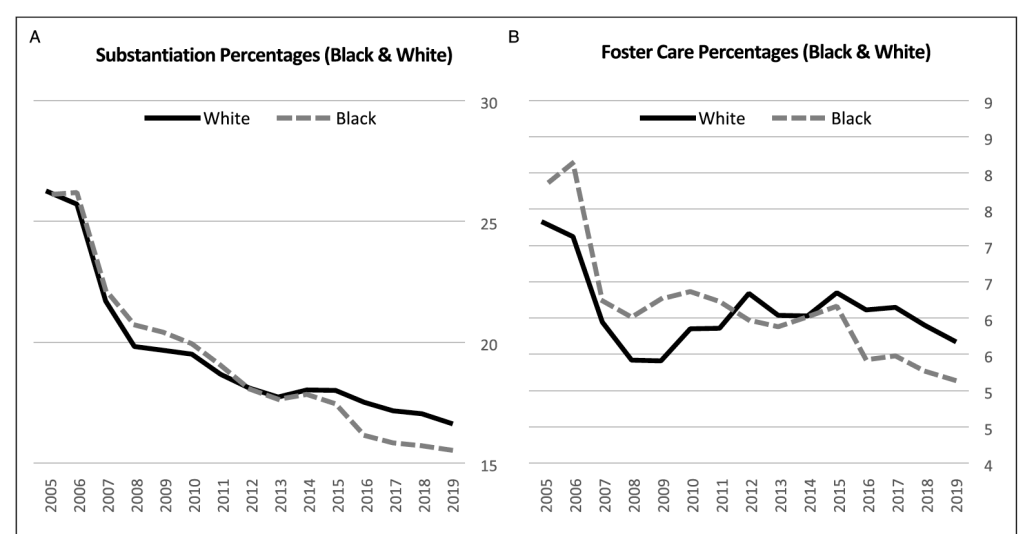

- Nationally, Hispanic children are reported to CPS at about the same rate as White children. Raw data shows them slightly more likely to be substantiated and placed in foster care once reported. See Brett Drake et al., Racial/Ethnic Differences in Child Protective Services Reporting, Substantiation and Placement, With Comparison to Non-CPS Risks and Outcomes: 2005–2019. ↩︎

- From U.S. Children’s Bureau, Child Maltreatment 2023, page 59. States reported that 6,04 per 100,000 Black children were found to be victims of a child maltreatment fatality compared to 1.94 per 100,000 White children. These are deaths that have been confirmed as due to maltreatment by child protective services, medical examiners, or police, a process that may be affected by bias. ↩︎

Addendum: Factual Errors in CFSA’s Mandatory Reporter Training Implicit Bias Module

The implicit bias module in CFSA’s mandatory reporter training curtains numerous factual errors and omissions. Here are a few.

- “National studies by the US Department of Health and Human Services reported that minority children and in particular black children are more likely to be in foster care than receive in-home services even when they have the same problems and characteristics as White children.” I asked the CFSA’s Communications Director for a citation and I found the exact language in one of the three references that were provided–a 2019 ABA brief entitled Race and Poverty Bias in the Child Welfare System: Strategies for Child Welfare Practitioners. A footnote referred readers to an essay by Dorothy Roberts for PBS’ Frontline program. That essay in turn attributes the same quote to “a national study of child protective services by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services” with no citation. When consulted, ChatGPT references the outdated 1996 National Incidence Survey of Child Abuse and Neglect, which has been superseded and contradicted by the more sophisticated study published in 2010.

- “Rates of child abuse are not higher for children of color than white children. People of color do not treat their children worse than White families do. Racial disproportionality in CW is due to systemic racism, cultural misunderstandings, stereotypes, and biases that influence the decision to report alleged child report or neglect to CPS.” This is simply not true. First, we don’t have definitive evidence of child abuse rates as it occurs in secret, may not be reported, and investigations may not come up with the right results. But all the evidence we have indicates that Black families do abuse and neglect their children more than White families. This is likely due to the history of slavery and racism, which led to higher poverty and concentration in impoverished neighborhoods characterized by crime, substance abuse, unemployment, and limited community services, as well as a legacy of intergenerational trauma associated with these factors as well.

- “Although African American families tend to be assessed with lower risk than White families, they are more likely to have substantiated cases, have their children separated, or be provided family based safety services.” I could not find any resource on the internet that indicates that Black families tend to be assessed with lower risk than White families It is true that Black children tend to have more substantiated cases, have their children removed, or receive in-home services. But that is before controlling for family characteristics that affect risk. The only research article cited by CFSA actually reported that when they controlled for family risk factors, agency and geographic contexts, and caseworker characteristics, Black children were not at significantly higher risk of substantiation or removal.