by Emily Putnam-Hornstein (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), Sarah Font (Pennsylvania State University), and Brett Drake (Washington University in St. Louis).

I am honored to publish this post by three of the leading academic researchers in child welfare. As often is the case in this blog, they are writing about the flawed use of data to support the user’s claims about a policy or program. In this essay, the authors discuss last year’s testimony by Indiana’s deputy director of child welfare services claiming success for the state’s family preservation program in reducing foster care caseloads without compromising child safety while also reducing racial disparities.

On May 22, 2024, the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance held a hearing titled “The Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA): Successes, Roadblocks, and Opportunities for Improvement.” The testimony was striking for its still-aspirational tone 6 years after the law passed and its sanitized depiction of why children enter foster care. As researchers, however, the statistics offered by Indiana’s deputy director of child welfare services, David Reed, caught our attention. Reed’stestimony indicated that FFPSA and associated investments in intensive family preservation services and concrete supports had produced: (1) a 50% decline in the state’s foster care caseload, alongside improved child safety; and (2) a two-thirds decrease in racial disparities among children entering foster care.

These claims are striking and beg the question: How?

On their very face, such dramatic numbers should invite skepticism. Despite continued efforts to move “upstream,” empirical studies of maltreatment prevention programs generally generate null or small effects. But one way for an agency to achieve a rapid reduction in foster care caseloads is to increase the threshold for intervening, leaving children in environments from which they would have been previously removed.

Below, we review data for Indiana and conclude that available evidence does not support the testimony offered.1 This is problematic not only for Senate Committee Members, but also the field at large. Bold causal claims based on flawed interpretations of data too often lead policymakers, and the public, to conclude that there are easy fixes to complex problems.

Reducing Entries to Foster Care and Improving Child Safety

The ideal way to reduce foster care entries is by reducing the community incidence of child abuse and neglect. Other than a brief drop during the COVID-19 pandemic, and despite investments in voluntary programs such as Healthy Families Indiana, referrals to Indiana’s child maltreatment hotline were largely stable pre- and post-FFPSA implementation (i.e., 168,919 in 2017 vs. 172,077 in 2023). There is no evidence of a decrease in suspected maltreatment identified by community members.

Of note, data indicate that Indiana is now screening in a smaller percentage of referrals (75.0% in 2017 to 57.9% in 2023). Certainly, it is possible that Indiana was responding to allegations of maltreatment that were unwarranted. Indiana issued guidance in 2021 designed to change the state’s response to allegations of “educational neglect.” But if such changes led to the reduction, one would expect that as more “low-risk” referrals were screened out, children who were screened in would have higher risk and a greater share would be identified as victims requiring services.

Yet that is not what the data show. Among children who were screened in, the number of substantiated victims declined by roughly 30% between 2017 and 2023. This decline is particularly notable, given that during this same period, overdose deaths in Indiana were increasing and parental substance abuse is one of the most well-established risk factors for child maltreatment. It would appear that in addition to reducing the number of children who received a response, Indiana also increased its threshold for substantiating maltreatment. Importantly, changes in substantiation thresholds affect not only overall child victim counts, but also the federal measure of repeat maltreatment, which is the indicator of safety cited in Reed’s testimony. The easiest way to document improvements in child safety is to raise the bar for substantiation, thereby reducing both the initial victim count and the likelihood of identifying repeat incidents.

Short of successful efforts to reduce the incidence of maltreatment in the community at large, a second way an agency could theoretically—and safely—reduce the number of children in foster care is by expanding efforts to prevent placement by providing more families with effective services and resources. Yet once again, Indiana’s data show that fewer rather than more children reported for maltreatment have received in-home services. State data suggest a reduced number of children receiving in-home services in absolute numbers (Figures 1 and 2, Table 1) and no change in the proportion (Figure 3). Moreover, as depicted in all three figures and consistent with screening and substantiations, steep declines in in-home services and foster care caseloads began in 2017, before FFPSA was implemented.

A third possibility is that the services provided have become more effective, thus reducing the rate of children entering foster care. Yet the major program touted by Reed in his FFPSA testimony—an intensive family preservation program called Indiana Family Preservation Services—appears to have no effect on removal and a near-zero effect on repeat maltreatment.2 Indeed, the program is described as having “0 favorable effects” by the federal clearinghouse for evidence-based programs. There is simply no way to attribute a 50% foster care reduction to Indiana’s prevention services.

Finally, because the number of children in foster care is a function of the number of children entering care relative to the number of children exiting care, an additional possibility is that Indiana found ways to transition children out of its foster care system faster or in greater numbers. However, foster care entries declined from 12,826 in 2017 to 6,212 in 2023. underscoring that the bulk of the 50% caseload reduction likely stemmed from fewer entries.

Decreasing Racial Disparities

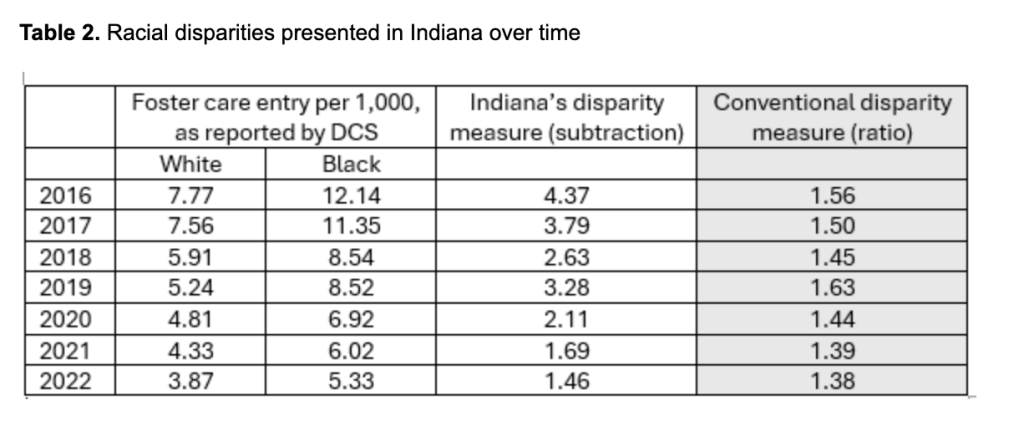

Senate committee members also heard about data suggesting that Indiana’s Black–White disparity in foster care entries declined by two thirds. The statistics presented, however, were quite unusual. The typical approach—both in the health literature and as a longstanding practice in child welfare—is to measure disparities as a ratio of rates (known as relative risk). In the context of the testimony presented, this would have been presented as the Black foster care entry rate divided by the White foster care entry rate.

But this is not what was used.

Rather, Indiana’s numbers were presented as the subtracted difference: the Black foster care entry rate minus the White foster care entry rate. The problem with this approach is that it is very sensitive to base rates. Imagine that rates of removal were 10 per 1,000 Black children and 1 per 1,000 White children, then those rates decreased to rates of 1 per 1,000 for Black children and 0.1 per 1,000 for White children. In both cases, the relative risk of removal is 10 times higher for Black children than White children (a 0% change in disparity). But using Indiana’s subtraction-based measure, it would appear that the disparity declined from 9 to 0.9: a 90% reduction.

Using the conventional disparity ratio formula, the Black–White removal rate disparity declined only slightly in 2021–2022 compared with 2016–2017—a reduction of roughly 12%, not the “66.9% decrease” indicated in Reed’s testimony (see Table 2).

Summary

Available data do not support testimony that FFPSA implementation and Indiana’s Family Preservation Services program led to a 50% decline in foster care cases. Likewise, any reported improvements in child safety are likely an artifact of changed thresholds for classifying child maltreatment victims. We also believe that this testimony indicating dramatic reductions in racial disparities is quite overstated.

Of course, it is always possible that we have misunderstood the numbers Reed referenced—which is why we contacted him almost a year ago and shared our analysis. We received no response. If there is additional data that supports the testimony provided, we hope it will be made available. Until then, it is only reasonable to conclude that the striking claims made do not hold up to even modest scrutiny.

Note: On June 3, 2025, the IndyStar published an op-ed by Emily Putnam-Hornstein and Sarah Font summarizing the analysis in this post.

Notes

- Regarding data published by Indiana’s Department of Child Services, we relied on publicly available information published as of June 2024 to align with what would have been available at the time this testimony was prepared. We also used data submitted by Indiana and found in the annual Child Maltreatment Reports. We focused on trends from 2017 (before FFPSA) through 2023 (the most recent year available).

↩︎ - To elaborate, the intervention produced no “direct effect” on children entering foster care (i.e., no statistically significant reduction occurred in placements among families who were served). Published research has indicated that the intervention may have led to a small reduction in repeat maltreatment. To be generous, Indiana officials might argue that despite no direct effect on removals, the reduction in repeat maltreatment led to reduced removals over time. However, the estimated reduction in repeat maltreatment is only 4%, meaning that any indirect effects on removals cannot be more than this 4%. It is also worth noting that the declines in foster care caseloads began long before the program was implemented at any scale in Indiana. ↩︎

Figures and Tables

The federal

The federal