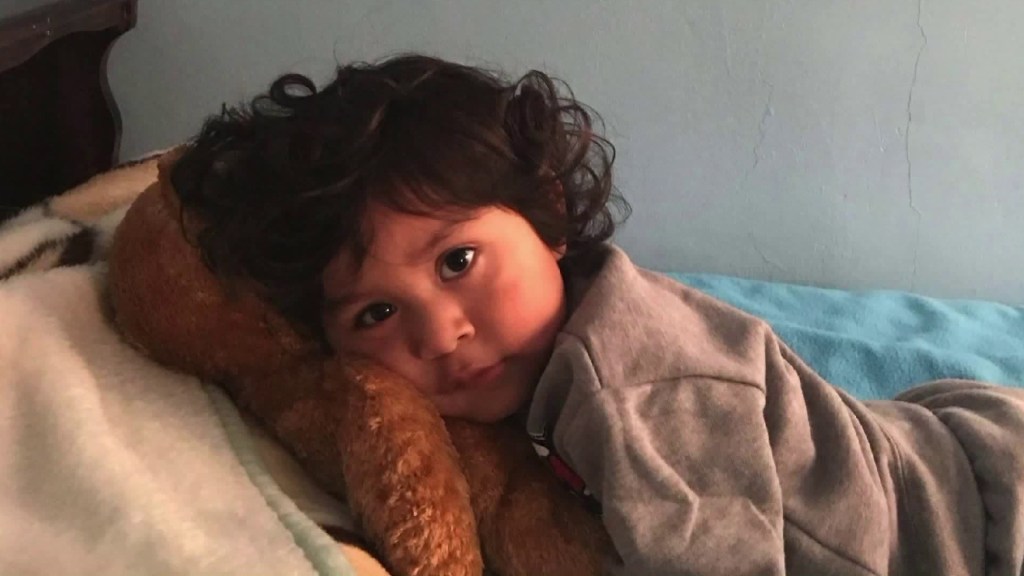

As many of my regular readers know, I have been fearful that the current climate emphasizing family preservation and racial and ethnic disparities in the child welfare involvement might end up inadvertently harming children. Well, it has happened in California, where a child is dead after the Department of Child and Family Services (DCFS) disregarded a court order to remove a child from a lethal home, motivated in part by hypersensitivity to concerns of possible bias and an exaggerated focus on family strengths that blinded agency staff to glaring problems.

On July 5, 2019, the parents of four-year-old Noah Cuatro called 911, saying their son had drowned in the pool at their apartment complex. But Noah did not look like a drowning victim. He had signs of strangulation, old and new rib fractures, and bruises across his chest, arms, and legs, and a large mark on his forehead. The cause of death was ruled as suffocation. His parents are facing trial for murdering and torturing him.

In August 2019, the Los Angeles Office of Child Protection (OCP) issued a flawed report that exonerated the Department of Child and Family Services of any responsibility for Noah’s death. Fortunately, the Los Angeles Times and the Investigative Reporting Program at UC Berkeley went to court to gain access to documents that would tell them what really happened. They reviewed juvenile court files, emails, and testimony from a grand jury proceeding that led to the indictment of Noah’s parents. In a harrowing article describing the results of their investigation, the journalists document the role of errors, misjudgments, bureaucratic conflict, bias accusations, and a flawed practice model that together “blocked multiple opportunities to protect Noah.” My account is based in part on the Times article as well as the OCP report, which contains some dates and other details that help flesh out the timeline of this tragic case.

Noah Cuatro was first removed from his parents in August 2014 when he left the hospital after birth, after his mother, Ursula Juarez, was alleged to have abused an infant half-sister, causing skull fractures. He ended up in the home of his great-grandmother, Eva Hernandez. At the age of nine months, he was returned to his parents when the agency was unable to prove the allegations against Juarez. But the Times-UC Berkeley investigation found that Noah’s parents always felt that DCFS had robbed them of the first nine months with their newborn. And Hernandez felt that perhaps because they missed his first nine months, they never bonded with Noah and therefore targeted him for abuse.

In November 2016 Kaiser Permanente called the child abuse hotline to report that Noah had missed eight doctor’s appointments over the spring and summer of 2016. An investigation found that Noah had gained only a few ounces between February 2015 and October 2016. His muscles were deteriorating, and he was unable to walk at the age of 27 months. Once again, Noah was removed from his parents and placed first in a facility for medically fragile children and then back with Hernandez.

Two years later, on November 9, 2018 Noah was returned to his parents by a court over the objections of DCFS. Noah had thrived with Hernandez, reaching the appropriate weight and height for his age. He screamed and wet the bed before and after visits with his parents and begged to stay with his great grandmother. Moreover, his parents had not complied with court orders to participate in therapy and visitation with Noah. But the Juvenile Court commissioner, Steven Ipson, saw “substantial progress” by the parents and sent Noah home, requiring that his parents arrange for a visitation schedule with Hernandez, participate in Parent Child Interaction Therapy with Noah, and send him to preschool.

The red flags appeared almost as soon as Noah returned to his parents. On her visits to the family, Susan Johnson, the social worker assigned to the case, learned that Noah’s parents were ignoring the court orders for therapy, preschool and regular visits with his great-grandmother. In April 2019, an aunt made a call to the child abuse hotline, reporting that Noah was losing weight and had thinning hair. Worse, he had changed from an exuberant boy to a scared one. Another relative had told her that during an overnight stay Noah had night terrors and complained of pain in his “butt.”

Johnson went to the home and found Noah with marks on his right arm and neck, a big bruise on his left arm, and lotion covering his back, which his mother attributed to eczema. When Johnson asked what happened when he did something wrong, Noah said “I get hit,” but he quickly retracted. She tried the same question again, and got the same affirmation and quick retraction–characteristic of a scared, abused child. Back at the office, Johnson met with her supervisor and a senior administrator, who told her to file a petition for removal.

But it was not Johnson’s job to assess the truth of the allegations. She was a “Continuing Services Children’s Social Worker” (CS-CSW) in DCFS lingo, whose job was to monitor and assist the families in their journey toward a safe home and case closure. The duty of investigating the allegations fell to an “Emergency Response Children’s Social Worker (ER-CSW often known as a Child Protective Services or CPS worker in other states) named Maggie Vasquez Ducos. When Vasquez Ducos visited the family, Juarez told her that Noah got his injuries by falling off a bunk bed. She also told her, in tears, that Johnson and DCFS had been persecuting her. Noah denied abuse, and a medical exam found that his injuries could have been caused by falling from a bunk bed.

Vasquez Ducos consulted with the social worker who worked with the family before Johnson, Lizbeth Hernandez Aviles. Hernandez Aviles reported that “she had always had concerns for Noah, was opposed to his return home, and felt that the parents are habitual liars who present well,” according to the OCP report. She expressed concern about the existence of bonding between Noah and parents and believed he was the child in the family targeted for abuse.

Nevertheless Vasquez Ducos made a finding of “inconclusive” on the new allegation, meaning that there was insufficient evidence to determine that child abuse had occurred, on May 9, 2019. There is no indication in the records reviewed by the Times and UC Berkeley that Vasquez Ducos reached any of Noah’s relatives, an essential component of any serious child abuse investigation. The police investigation after Noah’s death found text messages between relatives revealing their rising concern during the same time period about the parents’ treatment of Noah.

While Vasquez Ducos was investigating, Johnson was writing and submitting her petition for the removal of Noah and on May 15 it was granted by the court, along with the requirement that Noah be taken for a medical exam. On the same day, a new referral came in alleging domestic violence in the home and sexual abuse of Noah. Assigned to investigate the new referral, Vasquez Ducos learned of the removal order and immediately began to question the need for it. Parroting the words of Noah’s parents, she told her supervisor that Johnson was “harassing them.” She argued that Johnson was biased against the parents and overly influenced by great-grandmother Hernandez.

Investigating the new allegations, Vasquez Ducos visited the family on May 20, 2019, accompanied by the previous social worker, Hernandez Aviles, who had voluntarily taken a demotion to be a Human Services Aide due in part to the stress of managing Noah’s case, according to the Times-UC Berkeley investigation. They found Noah with an injury to his cheek, for which three explanations were given, along with plenty of coaching by Mom for Noah to endorse her explanation. During the visit, Hernandez Aviles reported that Noah “randomly” ran up to her stating ““They feed me a lot,” “They take good care of me,” and “They love me.” It’s hard to imagine better evidence of coaching, and indeed Hernandez Aviles noted that many of Noah’s responses appeared coached.

But Vasquez Ducos was unmoved. In a May 22 meeting with higher management, she argued against the removal order and the top administrator in the room took her side, telling Johnson not to execute the order.* It was agreed that DCFS would facilitate a “child and family team meeting” with the family. Johnson testified that when she tried to state her case, a supervisor elbowed her to be quiet. But she was heard to state, “that she didn’t want a dead kid on her watch,” according to an email quoted in the Times article. Ironically, the new allegation was cited as a reason not to remove Noah until the investigation could be completed. To make matters worse, Johnson, Noah’s main advocate, was removed from the case. It appears that the top administrator who made the decision not to enforce the court order also wanted a Spanish-speaking case manager, although such a person was never appointed and the job of managing the case for the rest of Noah’s life was left to Vasquez-Ducos, who was an investigator, not a case manager.

On June 6, Juarez, who had repeatedly denied being pregnant, gave birth to a baby boy. She had received no prenatal care and initially claimed to be a surrogate, despite lacking any paperwork, and tried to “sneak out of the hospital.” A Kaiser social worker informed DCF about the birth. She also told Vasquez Ducos that Kaiser’s psychiatric exam showed that Juarez had traits of a sociopath and indicated that she was worried about Juarez’ contradictory accounts of her pregnancy. Nevertheless. Vasquez Ducos and her supervisor decided to let Juarez go home with her newborn.

During the month of June, the family seemed to turn against Vasquez Ducos as well, apparently obstructing all her attempts to visit him before the end of the month. Her last visit with Noah was on June 28, 2018. According to the OCP report, Noah was described as “in good spirits and reported that he was doing well.” Vasquez Ducos reported that Noah’s father dismissed her attempt to schedule the long-delayed meeting with DCFS that was agreed at the May 22 meeting, saying they wanted no further involvement with the agency–a strange thing for a social worker to accept as the prompt scheduling of the meeting should have been a condition for keeping Noah at home.

In the final week of Noah’s life, Vasquez Ducos (perhaps sensing impending disaster and seeking justification) set her sights on the people who tried to protect Noah, stating in emails that Johnson was biased towards Noah’s family, that great-grandmother Hernandez (the only person who treated Noah like a mother) was at fault for biasing Johnson, and that Noah’s parents were victims of DCFS. “I feel like as a Department we have been picking on this family,” she wrote on July 3. Three days later Noah was dead.

A close reading of the Times-UC Berkeley article and the OCP report shows that DCFS disregarded numerous red flags that should have been obvious to any competent social worker with a modicum of training: the parents’ repeated failure to comply with the terms of their custody order; the admissions of abuse and subsequent retractions by Noah; his unsolicited comment that his parents treated and fed him well and other obvious signs of coaching; the assessment indicating that the mother had traits of a sociopath; and the comments by the previous social worker, among many others. There were multiple failures in case practice including the ignored removal order, the disregarded court order for a medical exam, the lack of response to the parents’ repeated failure to comply with the terms of their custody (a reason in itself for removal of the child); and the failure to schedule a family meeting which was an essential component of the plan to leave Noah at home.

But what makes this more than yet another story of missed red flags and bad case practice is the explicit evidence of the impact of two factors—bias accusations and “strength-based practice–in the death of Noah Cuatro.

Bias accusations

From the beginning of her involvement, Vasquez Ducos seemed to be convinced by Noah’s parents that Susan Johnson was biased against Noah’s parents. The charge of bias took place in the context of a state and national reckoning with racial and cultural bias against people of color. As I’ve written, there is a growing focus on the disparities in child welfare involvement between different racial and ethnic groups. These disparities are evident as they relate to Black and Native American children, who are much more likely to be reported to CPS, found to be abused or neglected, and placed in foster care, than White children. But this is not the case for Latinos like Noah, who actually are underrepresented in foster care nationally, constituting 25.4 percent of the child population but only 20.8 percent of those in foster care. In California, Latino children enter foster care at the same rate as all children–5.3 per thousand in the population, and in Los Angeles County they enter foster care at a slightly lower rate. Yet, “people of color” who are said to be over-represented in foster care and child welfare services are often assumed to include Latinos.

The extent to which Vasquez Ducos and her supervisors believed that Johnson (a Black woman) was biased against Latino families is unclear. The previous social worker, who had argued for removal, was Latina. The great-grandmother, who Vasquez-Ducos accused of influencing Jackson against Juarez, was also Latina. Yet, the Times reported that the administrator who quashed the removal order also wanted Johnson replaced with a Spanish-speaking social worker, even though the entire family was fluent in English except for one person in the extended family. Whatever the cause, the facile use of the bias label seemed to blind Vasquez Ducos to the evidence that should have been apparent to any minimally-trained investigative social worker.

The reporters found something very telling in Vasquez Ducos’ notes. She quoted Juarez as saying “Why would we hurt our baby when we just got him back? I have had this case open for four years, and I have been told I’m good enough to only have my two kids but not Noah. How does that make sense?” Apparently Vasquez Ducos agreed. She must have never learned about the well-known phenomenon of one child in a family being targeted for abuse, as well as the attachment problems that can ensue when an infant is apart from its mother from birth, information that one hopes is included in training for child protective services workers everywhere.

Strength-based practice

Perhaps even more important than the bias issue is the role that a “signature” DCFS policy played in Noah’s death. In telling testimony reported by the Times, Vasquez Ducos’ supervisor reported that “DCFS management wanted to follow the core “practice model” that requires workers to remain focused on the positive, taking a better look at a family’s strengths and less at its weaknesses.” Similarly, Hernandez Aviles told the grand jury that colleagues decided not to remove Noah in line with the agency’s “strength based approach.”

According to Los Angeles DCFS website, its social workers use a “Core Practice Model that prioritizes child safety while emphasizing strengths over deficits, addressing underlying needs over behaviors, and instilling empowerment over helplessness.” This Core Practice Model is an example of what is generally called “strength-based practice,” a theory of social work practice that emphasizes clients’ self-determination and strengths.

I am familiar with this approach because I was trained in a similar model by the District of Columbia’s Child and Family Services Agency. We learned that in the past, child welfare practice was characterized by an emphasis on deficits, telling parents what is wrong with them and what they must fix. This approach, we were told, created hopelessness among parents and interfered with the development of good relationships with social workers. We were told that strength-based practice empowers families to make positive self-directed change.

It makes sense find a family’s strengths, emphasize them to the family and build on them. I certainly tried to do this when I worked with families that were trying to get their children back from foster care. But to disregard problems that could lead to harm to a child in no way “prioritizes child safety” as DCF claims to do. Noah’s case shows how disregarding family problems despite numerous red flags can lead to tragedy.

But strength-based practice is in line with a national movement focusing on parents’ rights and stressing the importance of keeping families together, with removals eliminated or drastically restricted. This movement has been reinforced by the current racial reckoning, which has produce arguments that child protective services is nothing more than a “family policing system.” Noah’s case shows what can go wrong when this philosophy goes unchecked.

Bobby Cagle, the Director of DCFS, told the reporters that he saw no problems with his agency’s policies or its handling of Noah’s case. He refused to say if any employee was disciplined as a result. Firing people is not a solution to such unnecessary deaths as that of Noah. However, it seems likely that one or more people in the Lancaster office of DSS are so unsuited to their jobs that they pose a danger to children. Keeping them on the job is unacceptable on child protection grounds, not to mention the need for accountability.

The death of Noah Cuatro was a tragedy. The fear and suffering that he endured starting from the time he was returned to his parents at the age of four was also a tragedy. We cannot know many children are suffering at this very moment because social workers or their bosses miss the most obvious red flags due to ignorance, overwork or because their ideology or training does not allow them to see the glaring faults of their parents. DCFS’ Office of Child Protection tried to cover up this horrendous failure that cost the life of a child. The Los Angeles Times and UC Berkeley deserve kudos for providing the answers that OCP tried to cover up.

*According to OCP, a removal order authorizes, but does not require removal of a child. However the court must be notified within ten days if the child is not removed. Nobody notified the court that the removal order obtained by Johnson was not carried out until the hearing on June 25, more than 45 days after the order was approved. The ordered medical exam had never been carried out.

Thanks for this great article. Pure narcissistic enabling by people like Ducos

LikeLike