Image: Yadkin Ripple

by Marie Cohen

At a glance:

- Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD) is a diagnosis that is included in the DSM and often applied to foster and adopted children. While RAD refers to a pattern of inhibited, withdrawn behavior, some controversial therapies (often described as varieties of “Attachment Therapy”) are based on a distorted definition of RAD, or on an unauthorized diagnosis of “attachment disorder” that includes a deep-seated rage that if unaddressed will result in antisocial and even criminal behavior.

- Among the practices included these controversial therapies are severe disciplinary methods including the establishment of total parental control over children’s actions, including eating, drinking and using the toilet.

- Many of these Attachment Therapy technique include a component that involves forcing the child to express underlying rage through physically coercive methods that may include being held down by several adults for as much as three to five hours. Several child deaths have been attributed to such methods.

- In order to prevent more damage to children, it is necessary to adequately vet prospective adoptive parents for their readiness to parent children with challenging behaviors due to early trauma and deprivation. Even for parents who are able to meet the challenge, training and continued support are necessary.

- Unbelievably, some adoptive parents have not been charged even when their parenting techniques have led to the deaths of their children. It is absolutely necessary for parents who use abusive parenting techniques to be charged and tried in court. Adequate investigations are necessary in order to ensure that the conditions that lead to such cases are identified and remedied.

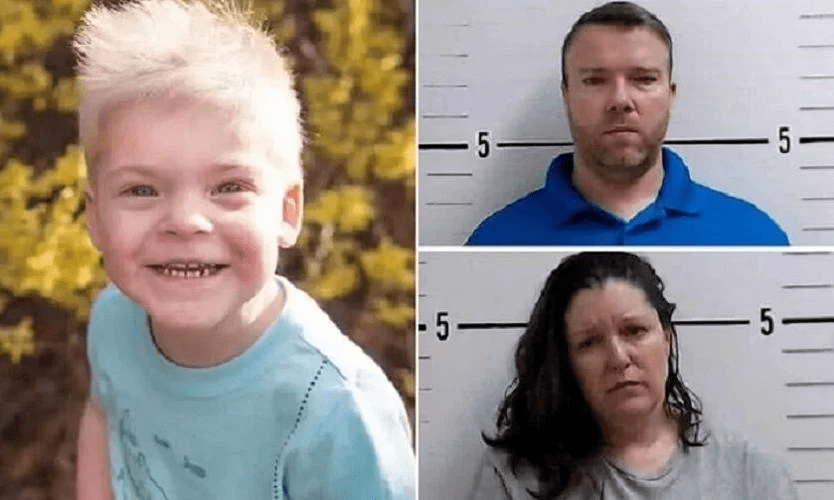

On January 5, 2023, according to a police warrant filed in Surry County, North Carolina, Joseph Wilson received a text from his wife telling him that something was wrong with their four-year-old adopted son Skyler after he was “swaddled.” She attached a picture of Skyler lying face down on the floor, wrapped in a sheet or blanket with duct tape attaching him to the floor. “Swaddling” is a practice used in many cultures to comfort infants, but Wilson told police he was referring to a parenting technique learned from a parenting expert named Nancy Thomas. (Court documents also state that one of the Wilsons’ former employees described recorded Zoom counseling sessions the couple had with Thomas.) Skyler died at Brenner Children’s Hospital in Winston-Salem on Jan. 9 of a “hypoxic, anoxic brain injury,” meaning that oxygen was unable to reach his brain due to the “swaddling.” Skyler’s adoptive parents, Jodi and Joseph Miller, have been charged with murder and felonious child abuse and are awaiting trial, which has recently been postponed–for the second time–from June 2 to December 1, 2025.

After Skyler’s death, police recovered surveillance cameras and arm and ankle restraints that Wilson had told them his wife used on Skyler during “swaddling.” A former foster parent of Skyler and his brother told police that Jodi Wilson had told her about using practices like “food restriction, the gating of Skyler in a room for excessive ‘alone’ time, and the exorcisms of both children.” The former foster parent was concerned enough to call Child Protective Services a month before the incident that killed Skyler.

Nancy Thomas, mentioned as the source of the swaddling technique and as a counselor to Skyler’s parents, is perhaps the most prominent exponent of a group of approaches to that the American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children (APSAC) described in a 2006 report as “controversial attachment therapies.” These therapies are generally directed at children with “attachment disorders.” The only such disorder that is officially recognized by the mental health community is “Reactive Attachment Disorder” (RAD), a diagnosis that is included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). This diagnosis involves “a consistent pattern of inhibited, emotionally withdrawn behavior toward adult caregivers” as well as a “persistent social and emotional disturbance characterized by behaviors like minimal responsiveness to others, limited positive affect, and “episodes of unexplained irritability, sadness or fearfulness.” To be diagnosed with RAD, the child must have “experienced a pattern of extremes of insufficient care,.” which explains why this diagnosis is often applied to children who were adopted from orphanages abroad or foster care in the US. Some practitioners of these controversial attachment therapies, like Nancy Thomas, prefer to speak of children with “attachment disorder,” which is not included as a diagnosis in the DSM. Others use the term RAD but ascribe to that term a variety of symptoms that are not part of the DSM definition.

Whatever term they use, practitioners of controversial attachment therapies tend to believe that children who experience early adversity become “enraged at a very deep and primitive level.” This suppressed rage is said to prevent the development of attachment to caregivers and others and to lead to severe behavioral problems, such as violent behavior. These children are described as failing to develop a conscience, not trusting others, seeking to manipulate and control others, and at risk of developing criminal and antisocial behaviors. According to Nancy Thomas, some famous people with “Attachment Disorder” who did not get help in time include Adolph Hitler, Saddam Hussein, Jeffrey Dahmer, and Ted Bundy.

As described in the APSAC report, these controversial attachment therapies suggest that “parenting a child with an attachment disorder is a battle, and winning the battle by defeating the child is paramount.” Parents are often counseled to start by establishing total control over all the child’s actions, and requiring immediate obedience to parental commands. Nancy Thomas’s book, When Love Is Not Enough: A Guide to Parenting Children with RAD-Reactive Attachment Disorder, includes advice like “In the beginning, your child should learn to ask for everything. They must ask to go to the bathroom, to get a drink of water, EVERYTHING. When it starts to feel that they must ask to breathe, you are on the right track.” Another quote: When given directions it is unacceptable for the child to ask ‘”‘why?” or ‘what?’ NEVER answer these questions….Remember, have a consequence ready when a rule is challenged.” Thomas also recommends putting an alarm on a child’s bedroom door, and the window if necessary. Other techniques that have been recommended by attachment therapists include keeping the child at home (even counseling home schooling), barring social contact with others, assigning hard labor or repetitive tasks, and requiring prolonged motionless sitting.

Many proponents of controversial attachment terapies also believe that a child’s rage must be “released” before he or she can function normally. This release is often provided through physically coercive methods that may include being held down by several adults for as much as three to five hours. These techniques can be traced to “holding therapy,” a technique developed by a child psychiatrist named Foster Cline, who was ackhowledged as a mentor by Nancy Thomas in her book. Cline was admonished and restricted from using parts of his holding therapy model by the Colorado Board of Medical Examiners after members saw video of an 11-year-old being subjected to physical and verbal abuse while being restrained.

“Holding therapy” and similar methods designed to address “attachment disorder” have been implicated in the deaths of several adopted children, including that of three-year-old Krystal Tibbets, who died in 1997 when her adoptive father “applied the full weight of his body on the girl by lying across her and pressing his fist into her abdomen,” a technique he said he was taught by a therapist; four-year-old Cassandra Killpack, who in 2002 was forced to guzzle two quarts of water while her arms were bound, and 10-year-old Candace Newmaker, who suffocated in 2000 by a “therapist named Connell Watkins during a 70-minute “rebirthing ceremony” that was supposed to treat her attachment disorder. Nancy Thomas was working for Watkins at the time of Candace’s death. The “swaddling” technique that killed Skyler Wilson is an example of such a method.

Advocates of controversial attachment therapies have come to the defense of Skyler Wilson’s parents. The President of the Board of a nonprofit called Attach Families, Inc. shared an article on Facebook about Skyler’s death with the following preface: “These tragedies are always written one sided with no Investigative reporting, sadly…They obviously were using a swaddling technique that some Professionals promote for Attachment. This is a tragedy. But before these parents are “burned at the cross” our Families want more information.” The Page also posted this: “As we have seen hundreds of others making our Families look like monsters. When the truth is we try and will try ANYTHING to help our children. This is what we are trying to help them heal from before they get too big for us to physically handle their rages. Rages in which they inflict self harm. Rages where they slam their heads over and over on purpose. Rages in which we try to protect them from themselves and others around them. If you don’t live it 24 hours a day you have no idea what it is like.” Attached was an article about a Kansas teen who was arrested in the killing of his mother. The article contained no details about the teen or his mother. It is hard to understand how this talk of rage would apply to four-year-old Skyler. His former foster parent told a reporter that Skyler “was so tiny and small but had a heart three times bigger than he was…”

In some cases, the parents themselves, after reading misleading literature about children with RAD may invent their own disciplinary practices or use those inherited from their own upbringings or family traditions. The Denver Post recently wrote about Isaiah Stark, a seven-year-old who died in 2020 from ingesting too much sodium, likely from drinking olive brine. The newspaper learned that Isaiah’s adoptive parents were forcing him to eat olives and drink olive brine as a form of punishment for his behavior. According to a report from the state’s Child Fatality Review Team, the mother blamed all of Isaiah’s difficult behaviors on RAD and both parents attributed his actions to “manipulative behaviors and wilfulness.” At the funeral, she described Isaiah’s death as “God rescuing him.”

Isaiah Stark’s parents were never charged for his death. Since there was no trial, the public never learned whether the parents received any sort of parenting advice from an “expert.” The failure to charge parents who have tortured and killed adoptive children is all too common: witness the case in Florida of Begidu Morris, whose parents were not charged after starving, confining and beating him for years, ostensibly because the person who actually killed him could not be determined. As developmental psychologist Jean Mercer writes, plea bargains and the failure of investigators to follow up on the development of abusive parenting practices mean that we often don’t know whether abusive parents drew on outside influences or their own family histories or imaginations for the practices that led to a child’s injury or death.

Concern about controversial theories and methods of “Attachment Therapy” about twenty years ago prompted the formation of a task force of the American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children, the leading professional society of professionals who deal with child abuse and neglect. Its 2006 report, mentioned above, concluded that “attachment parenting techniques involving physical coercion, psychologically or physically enforced holding, physical restraint, physical domination, provoked catharsis, ventilation of rage, age regression, humiliation, withholding or forcing food or water intake, prolonged social isolation, or assuming exaggerated levels of control and domination over a child are contraindicated because of risk of harm and absence of proven benefit and should not be used.” The report cautioned child welfare systems not to tolerate any such techniques by foster or adoptive parents. It also stated that “[p]rognostications that certain children are destined to become psychopaths or predators should never be made based on early childhood behavior.” It also condemned “intervention models that portray young children in negative ways, including describing certain groups of young children as pervasively manipulative, cunning or deceitful.”

Some adults are simply not suited to raise challenging children. Yet, agencies desperate to get children adopted, especially children with special needs in foster care, have placed children with such parents despite red flags, or even returned them after abuse was uncovered. In an extreme case in 2016, the 12-year-old adopted daughter of Eugenio and Victoria Erquiaga ran away from home. Neighbors found her with her hands zip-tied and her feet bound. She reported that she was locked inside a small playhouse for long periods of time with no bathroom. The story became national news and it became known that the parents had sought help from a mental health counselor who oversaw a program called “Radical Healing,” which no longer exists. The state charged the parents with child abuse. However, they then offered to drop all of the charges and expunge their records if the Erquiagas agreed to take their daughter back into their home, which they did. The girl ended up in a group home after she turned 18.

Twenty years since the APSAC report, children continue to suffer and die because they have been diagnosed by “experts” or parents with RAD or “attachment disorder.” To prevent more damage to children, state governments must adopt policies to ensure that all adoptive parents are adequately vetted. Agencies must be prepared to screen out potential adoptive parents who lack the patience, self-control and emotional intelligence to raise challenging children, and those who might be susceptible to practitioners offering controversial methods involving harsh discipline and physical restraint to cope with behaviors stemming from previous trauma or deprivation. In 2012, a committee led by Washington’s child welfare agency and children’s ombudsman published a Severe Abuse of Adopted Children Committee Report, which made several recommendations for improving assessment of assessing prospective adoptive families. These included strengthening qualifications for individuals conducting adoption home studies and post-placement reports and enhancing minimum requirements for these home studies and reports.

Training and ongoing support must also be provided to those adoptive parents who are deemed capable of accepting the challenge of raising children with histories of trauma and deprivation. These parents must be prepared to understand the needs and possible behaviors of the children they adopt, given their backgrounds. They also must be educated about the existence of parenting practices and therapies which are not supported by research and potentially harmful to children. And finally, they need ongoing support. The need for a greater investment in post-adoption services has been publicized by authorities like the Donaldson Adoption Institute (now closed) in its major report, Keeping the Promise: The Critical Need for Post-Adoption Services to Enable Children and Families to Succeed. Even RAD parent advocacy organizations like Attach Families Inc. are also asking for ongoing support.

Parents caught confining, starving, or otherwise abusing their children through adherence to “attachment therapies” must receive a criminal trial. This is, not only to ensure that justice is done, but also to provide an understanding of the factors that allow such tragedies to occur. The failure to try cases of parents who were obviously responsible for the torture and death of a child is a national stain and must be addressed.

That vulnerable children who have already been traumatized or deprived in early childhood in have met suffering or even death in licensed foster or adoptive homes should be a source of shame to all Americans. It is time to put an end to the suffering of children who have suffered enough. These tragedies can and must be prevented.

Just before this article went to press, the author became aware of media reports about the arrest of the adoptive parents of a 15-year-old boy, who for the past ten years has been locked in his bedroom for most of the day with no access to food, water or a bathroom. The adoptive father is a former employee of the El Paso County, Texas sheriff’s office. So far there has been no information about the genesis of the situation and whether a diagnosis or behavioral problem was involved. But it seems that hardly a week goes by without news of an egregious case of abuse against and adopted child. There is no time to waste in taking action to prevent more such suffering and damage to children.

This post was edited on June 24, 2025 to add a reference to the Washington report on severe abuse of adopted children and its recommendations and again on June 26 and 27 to correct several small errors and typos.