by Marie Cohen

Proposed federal budget cuts to child welfare services might hurt New Jersey’s recent progress in child welfare, the Commissioner of New Jersey’s Department of Children and Families told state legislators last month. The anticipated reduction of more than $100 million would force the department to “revert to its most basic role — that of child protection — not prevention, not support or empowerment, just surveillance and foster care,” DCF Commissioner Christine Norbut-Beyer told members of the state Senate’s Budget Appropriations Committee. The relegation of child protection–or “surveillance and foster care”–to the “most basic” version of child welfare is telling. DCF’s Commissioner, like many other progressive child welfare administrators, no longer views child protection as the primary purpose of child welfare services.

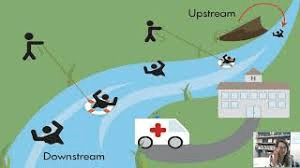

For those who regularly read this blog, the devaluation of child protection and foster care by a high-level administrator over child welfare will not be a surprise. There has been a sea-change in child welfare over the past decade. The mainstream view of the purpose of child welfare has shifted from responding to child abuse and neglect to “upstream prevention.” And why not? Why wait until children are abused and neglected if we can prevent the maltreatment altogether?

There is no denying that ideally, it is better to prevent maltreatment than to respond to it. But the services that are discussed as prevention are mainly in the province of other agencies. In seeking to broaden child welfare services through the Family First Act, Congress added mental health, drug treatment, and parenting training. While the latter can be seen as a function of child welfare, drug treatment and mental health are separate systems. There has been increased emphasis on cash and housing and other antipoverty benefits as child maltreatment prevention; we have large programs to address these problems–much larger than the child welfare system. Even some of the “prevention services” that DCF and other state agencies have adopted, like “Family Success Centers,” provide a wide array of place-based services, most of which do not fall into the traditional orbit of child welfare and would be most appropriately funded jointly with other agencies.

If “prevention” could abolish the need for child protection, then there would be no need for child protection agencies. But we know that no amount of “prevention” (at least as envisioned by today’s child welfare establishment) will eliminate child abuse and neglect. We are often talking about patterns of mental illness, drug abuse, family violence, and poverty that have persisted over generations. And then there are families that are not poor or characterized by generations of dysfunction but where a parent’s mental illness or disordered personality makes them incapable of safely raising children. As Jedd Meddefield describes in his brilliant essay called A Watershed Perspective for Child Welfare, “As critical as it is to fully consider upstream factors, it would be wrong not to do all we can to help children who lack safe families today.

But the fact is that many of today’s child welfare leaders like Norbut-Beyer appear not to be interested in child protection and foster care. They often disparage the “reactive” role of child protective services in contrast to the “proactive” nature of prevention. Many agencies have reactive missions–police, firefighters, emergency rooms–and one could argue these are the most important services of all because they save lives. The analogy with the police is revealing. Police react to allegations of crime just as child welfare agencies react to allegations of child abuse and neglect. To prevent crime, we must not rely on the police, who are overburdened already and not trained and equipped to provide the services needed. Instead we must turn to a whole host of agencies dealing with education, public health, mental health, housing, income security and more–the same agencies that we must mobilize if we want to prevent child abuse and neglect. Nobody is saying that the police need to address the underlying causes of crime.

Norbert-Beyer’s use of the word “surveillance” as a synonym for child protection is telling indeed. She clearly doesn’t see CPS investigators as heroes who go out in sometimes dangerous and certainly uncomfortable circumstances to protect children–and maybe even to save them. It’s not surprising because we have all been told that saving children is not what child welfare is about.1 And foster care? Norbert-Beyer boasts that New Jersey has the lowest rate of child removal in the country, and children who are removed more often than not go to relatives. She’s not very interested in the quality of care these vulnerable young people receive or in all the things her agency could do it improve it, like establishing foster care communities (like Together California) to house large sibling groups or investing in cutting-edge models of high-quality residential care.

When the person who is in charge of child protective services in a state that is acknowledged as a leader in the field calls it “surveillance,” and relegates it along with foster care to “basic” functions that hardly deserve mentioning, it’s hard to have faith that the crucial mission of child protection will be implemented with the passion it deserves. Norbert-Beyer’s comments illustrate the prevalent thinking that leads to the diversion of resources from crucially needed child protective services and foster care to “prevention services” that are and should be provided by other agencies.

- See for example this statement from Casey Family Programs, which includes the words “We must continue to evolve from an approach that seeks to “rescue” children from their families to one that invests in supporting families before abuse and neglect occur.” One of the first messages I was given as a CPS trainee is that my job was not to save children.

↩︎