by Marie Cohen

In a post dated January 10, 2025, I reported that 40 percent of investigations conducted by the District of Columbia’s Child and Family Services Agency (CFSA) in Fiscal Year(FY) 2024, which ended on September 30 2024, were “incomplete.” But by annual rather than quarterly data, that post actually understated the magnitude of the problem, which has worsened in the first half of FY 2025. The percentage of investigations that were terminated with a finding of “incomplete” increased to 65 percent in the second quarter of FY2025. The number of substantiated investigations has increased, while foster care placements and in-home case openings have not kept up with the apparent need for services.

The number of reports to child abuse hotlines varies by season, with reports tending to drop off during the summer when schools are closed and then increase again when schools re-open, along with fluctuations during the school year. Thus, data for part of a year should be compared to the same period of the preceding year. As shown in the table below, the number of reports to the CFSA hotline increased by from 11,945 in the first half of FY 2024 to 12,342 in the first half of FY 2025. The number of reports accepted for investigation actually decreased from 2,197 to 1,973, mostly because the hotline was screening out more of them. Nevertheless, the number of investigations conducted increased from 1,774 to 2,089. Thus, there were more reports, fewer reports accepted, and more reports investigated in the first half of FY 2025 than in the same period of the previous year. The reasons for these changes are unknown.

Table 1: Data for First Half of 2025 Compared to First Half of 2024

| October-March 2024 | October-March 2025 | |

|---|---|---|

| Hotline Calls (referrals) | 11,945 | 12,342 |

| Referrals Accepted for Investigation | 2,197 | 1,973 |

| Investigations | 1,774 | 2,089 |

| –Incomplete | 456 (26%) | 1,305 (62%) |

| –Unfounded | 949 (54%) | 327 (16%) |

| –Substantiated | 267 (15%) | 377 (18%) |

| –Inconclusive | 94 (5%) | 74 (4%) |

| In-Home Cases Opened | 125 | 169 |

| Children Placed in Foster Care | 110 | 96 |

An investigation can have several findings. “Substantiated” means that the investigator (with approval from their supervisor) has concluded that the allegation of maltreatment (or risk of maltreatment) is supported by the evidence. “Unfounded” means there is insufficient evidence to support the allegations. “Inconclusive” means there is some evidence that maltreatment occurred but not enough evidence to support it definitively. “Incomplete” is defined as “an investigation finding for referrals in which there were barriers to being able to complete every aspect of the investigation. This could include obtaining confirmation during the investigation that the family was a resident of another state outside D.C., the parent refusing the social worker access to the home to complete a home assessment, or inability to locate the family.” (For the complete definitions, see the Investigations Page on the CFSA Dashboard). It is important to note that “Incomplete” refers to a finding upon closure of an investigation. It is not refer to an investigation that is ongoing.

The total number of investigations increased from 11,945 in the first half of FY 2024 to 12,342 in the first half of Fiscal Year 2025, as Table 1 shows. And there were some big changes in the numbers of investigations that were incomplete, substantiated and inconclusive. The number of incomplete investigations skyrocketed from 456 to 1,305. The number of unfounded investigations dropped from 949 to 327. And the number of substantiated investigations increased from 267 to 377, which is a large increase of 41 percent. This reflects both an increased number of investigations conducted and an increase in the percentage substantiated from 15 percent to 18 percent.

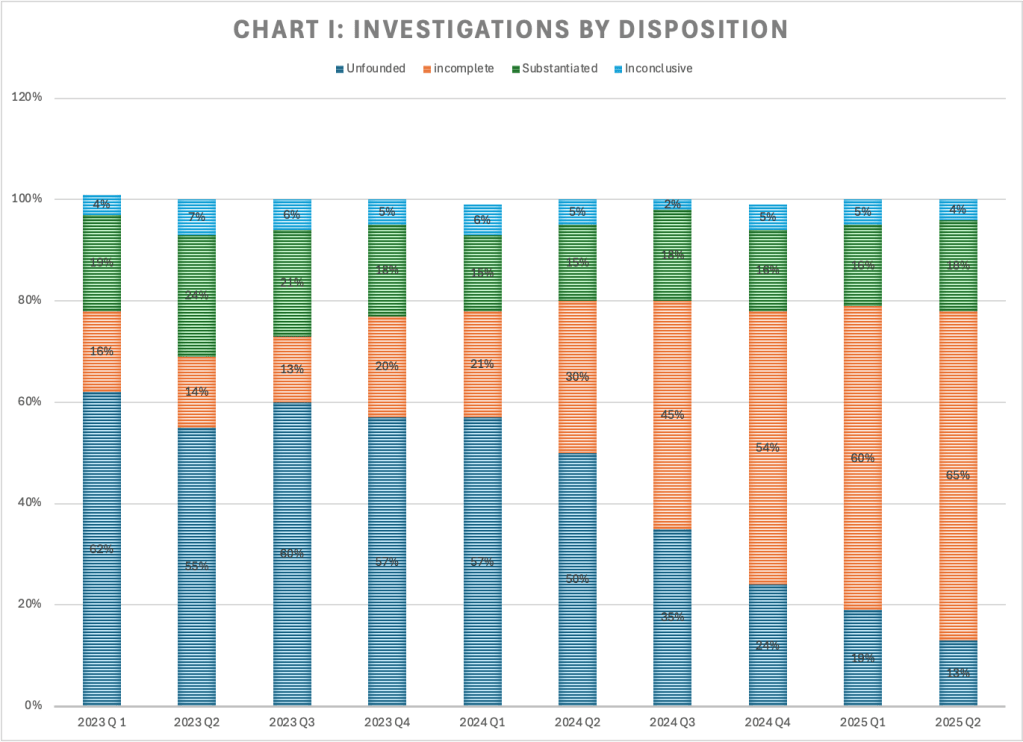

Chart I shows how the percentage of investigations by disposition has changed over the past nine quarters. The percentage of investigations that was incomplete (see the orange segments in the chart below) began to rise in the first quarter of 2024, when it jumped to 20 percent from 13 percent in the previous quarter. It rose to 30 percent in the third quarter of 2024, 45 percent in the third quarter, and 54 percent in the fourth quarter, 60 percent in the first quarter of 2025, and 65 percent in the second quarter of the current fiscal year.

As the percentage of investigations that are incomplete has increased, the percentage that are unfounded (dark blue in the above chart) has decreased–from 57 percent in the first quarter of 2024 to 13 percent in the first quarter of 2025. That drop of 44 percentage points happened at the same time as the percentage of investigations that were incomplete rose from 21 percent to 65 percent–an increase of 43 percentage points. It appears that investigations that would formerly have been closed as unfounded are now being closed as incomplete. CFSA did not respond to a request for the reasons for this change. The percentage of investigations that are substantiated has changed little since the first quarter of FY 2024.

Once an investigation is substantiated, CFSA may open a case for in-home services, or less often for foster care. As shown in Table I above, 169 in-home cases (each involving one or more children) were opened in the first half of FY 2025, compared to 125 in the first half of FY 2024. And 96 children were placed in foster care in the first half of FY 2025 compared with 110 in the first quarter of FY 2024. Unfortunately these two sets of numbers are not comparable as each in-home case can involve more than one child. But with substantiated reports increasing by over 100, in-home cases increasing by only 44, and foster care removals decreasing, it appears that some of the families with substantiated reports in 2025 are not receiving any CFSA services at all, and that is concerning. Perhaps some of these families are being referred to the collaboratives for services, which are less intensive and delivered by staff with lower credentials. And it is possible that some of these investigations may culminate in an informal kinship placement, but that means no services are provided to the parents or the children.

Clearly the staffing crisis with which CFSA (along with other agencies around the country) is struggling is responsible for the increase in incomplete investigations, and perhaps for the reduced percentage of substantiated cases receiving services as well. At the oversight hearing on February 13, 2025, Interim Director Trice pointed out that the number of investigative social workers has dropped from 100 to below 40. It is no surprise that CFSA’s oversight responses documented that most investigative workers had caseloads above 15. the maximum caseload allowed by CFSA’s Four Pillars Performance Framework. Average caseloads for the 38 investigative workers in the first quarter of FY 2025 were 30 or higher for 10 workers and 20 or higher for a total of 20 workers.

Director Trice reported that the agency is making do by diverting workers from the In-Home units to Investigations, but that is not a good solution. Families with in-home cases are often deeply troubled, with long histories of chronic neglect. According to CFSA’s 2023 Child Fatality Report, two children died while their families had open in-home cases. We cannot afford to divert these critically needed workers. Moreover, it is possible that the diversion of in-home workers to investigations may be part of the reason that in-home case openings did not increase more given the increase in substantiations. With workers not available to handle these cases, the agency may be more reluctant to open them.

What can be done? Creative solutions are needed. It may be necessary to temporarily reduce licensing or degree requirements through a special waiver due to the staffing crisis. Former Director Robert Matthews spoke of obtaining permission from the Board of Social Work Examiners to use workers with Bachelor of Social Work degrees to help investigators (not carry cases), but this plan was not mentioned in this year’s oversight responses. The agency might consider recruiting federal workers who have lost their jobs for these positions. Recruiting retired police officers and military veterans is another idea that has potential. A partnership with local schools of social work, as Maryland and other states maintain, is long past due. Those who agree to take jobs and remain for a given amount of time should receive loan forgiveness and perhaps housing as well. In a housing-hungry citizen, this could be a game changer. CFSA needs to think outside the box to resolve the staffing crisis.

CFSA’s Dashboard data for the first half of FY 2025 raises more questions than it provides answers. The most striking trend is the continuing explosion in the percentage of investigations that were incomplete–which was 65 percent in the second quarter. Also concerning is the failure of in-home case openings and foster care placements to keep up with increased substantiations. Like many other child welfare agencies, CFSA has been devoting much time and attention to programs outside of its core functions, like the warmline and family success centers. In this time of budget stringency and looming recession, it is time for CFSA to focus on its ability to perform its most basic and important function–child protection.