A long-awaited report from the federal government shows that most states saw a decrease in their foster care population during the fiscal year ending September 30, 2020, which included the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Both entries to foster care and exits from it declined in Fiscal Year (FY) 2020 compared to the previous fiscal year. These results are not surprising. Stay-at-home orders and school closures beginning in March 2021 resulted in a sharp drop in reports to child abuse hotlines, which in turn presumably brought about the reduction in children entering foster care. At the other end of the foster care pipeline, court shutdowns and a slow transition to virtual operations prolonged foster care stays for many youths. One result that is surprising, however, is the lack of a major decrease in children aging out of foster care, despite the widespread concern about young people being forced out of foster care during a pandemic.

Ever since the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in lockdowns and shut down schools around the country, child welfare researchers have been speculating about the pandemic’s impact on the number of children in foster care. While many states have released data on foster care caseloads following the onset of the pandemic, it was not until November 19, 2021 that the federal Children’s Bureau of the Administration of Children and Families (ACF) released the data it received from the 50 states, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico for Fiscal Year 2020, which ended more than a year ago on September 30, 2020. The pandemic’s lockdowns and school closures began in the sixth month of the fiscal year, March 2020, so its effects should have been felt during approximately seven months, or slightly over half of the year. The data summarized here are drawn from the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis System (AFCARS) report for Fiscal Year 2020 compared to the 2019 report as well as an analysis of trends in foster care and adoption between FY 2011 and FY 2020. State by state data are taken from an Excel spreadsheet available on the ACF website.

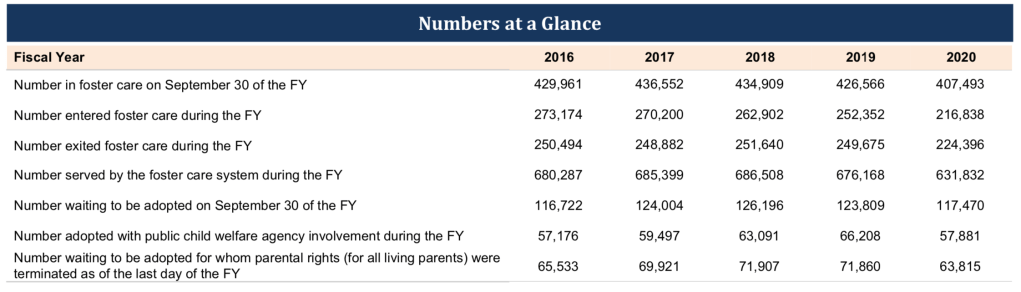

The nation’s foster care population declined from 426,566 on September 30, 2020 to 407,493 children on September 30, 2021. That is a decline of 19,073 or 4.47 percent. According to the Children’s Bureau, this is the largest decrease in the past decade, and the lowest number of children in foster care since FY 2014.* Forty-one states plus Washington DC and Puerto Rico had an overall decrease in their foster care population, with only seven states seeing an increase. The seven states with increases were Arizona, Arkansas, Illinois, Maine, Nebraska, North Dakota and West Virginia. The change in a state’s foster care population depends on the number of entries and the number of exits from foster care. And indeed both entries and exits fell to historic lows in FY 2020. The reduction in entries was even greater than the fall in exits, which was why the number of children in foster care declined rather than increasing.

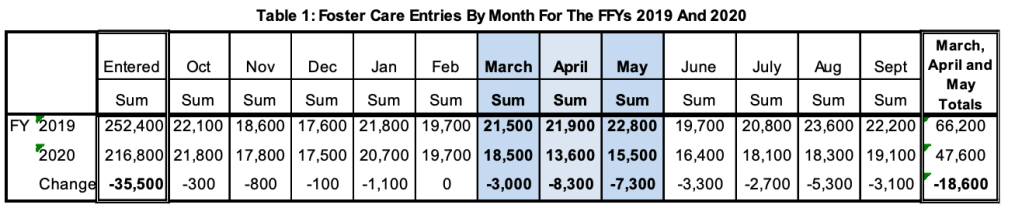

Entries into foster care fell drastically around the country, from 252,352 in FY 2019 to 216,838 in FY 2020 – a decrease of 14 percent. This was the lowest number of foster care entries since AFCARS data collection began 20 years ago. Foster care entries dropped in all but three states – Arkansas, Illinois, and North Dakota. These three states were also among the seven states with increased total foster care caseloads. It is not surprising that entries into foster care dropped in the wake of pandemic stay-at-home orders and school closings. While we are still waiting for the release of national data on child maltreatment reports in the wake of the pandemic, which are included in a different Children’s Bureau publication, media stories from almost every state indicate that calls to child abuse hotlines fell dramatically. This drop in calls would have led to a fall in investigations and likely a decline in the number of children removed from their homes. Monthly data analyzed by the Children’s Bureau drives home the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on foster care entries. More than half of the decrease in entries was accounted for by the drops in March, April, and May, immediately following the onset of stay-at-home orders, which were later relaxed or removed, as well as school closures.

Reasons for entry into foster care in FY 2020 remained about the same proportionally as in the previous year, with 64 percent entering for a reason categorized as “neglect,” 35 percent for parental drug abuse, 13 percent for physical abuse, nine percent for housing related reasons and smaller percentages for parental incarceration, parental alcohol abuse, and sexual abuse. (A child may enter foster care for more than one reason, so the percentages add up to more than 100.)

Exits from foster care also decreased nationwide from 249,675 in FY 2019 to 224,396 in FY 2020 – a decrease of 10 percent – a large decrease but not as big as the decrease in entries, which explains why foster care numbers decreased nationwide. Only six states had an increase in foster care exits: Alaska, Illinois, North Carolina, Rhode island, South Dakota and Tennessee. Along with the decrease in exits, the mean time in care rose only slightly from 20.0 to 20.5 months in care, while the median rose from 15.5 to 15.9 months in care. Again, it is not surprising that the pandemic would lead to reduced exits from foster care. In order to reunify with their children, most parents are required to participate in services such as therapy and drug treatment, to obtain new housing, or to do other things that are contingent on assistance from government or private agencies. Child welfare agency staff and courts are also involved the process of exiting from foster care due to reunification, adoption, or guardianship. All of these systems were disrupted by the pandemic and took time to adjust to virtual operations. Monthly data shows that about 68 percent of the decrease in exits was accounted for by the first three months of the pandemic, when agencies and courts were struggling to transition to virtual operations. It is encouraging that the number of exits was approaching normal by September 2020; it will be interesting to see if the number of exits was higher than normal in the early months of FY 2021.

Most exits from foster care occur through family reunification, adoption, guardianship, and emancipation. The proportions exiting for each reason in FY 2020 remained similar to the previous year, while the total number of exits dropped, as shown in Table 3 below. Children exiting through reunification were 48 percent of the young people exiting foster care in FY 2020, and the number of children exiting through reunification dropped by 8.3 percent from FY 2019. Children exiting through adoption were 26 percent of those leaving foster care, and the number of children exiting through adoption fell by 12.6 percent. Exits to guardianships fell by 11 percent and other less frequent reasons for exit fell as well. The drop in reunifications, adoptions and guardianships is not surprising given court delays and also the likely pause in other agency activities during the pandemic. However, nine states did see an increase in children exiting through adoption.

Table 3

Reasons for Exit from Foster Care, FY 2019 and FY 2020

| Exit Reason | FY 2019 Number | FY 2019 Percent | FY 2020 (Number) | FY 2020 (Percent) | Decrease (Number) | Decrease (Percent) |

| Reunification | 117,010 | 47% | 107,333 | 48% | 9,677 | 8% |

| Living with another relative | 15,422 | 6% | 12,463 | 6% | 2,959 | 19% |

| Adoption | 54,415 | 26% | 56,568 | 25% | 7,847 | 12% |

| Emancipation | 20,445 | 8% | 20,010 | 9% | 435 | 2% |

| Guardianship | 26,103 | 11% | 23,160 | 10% | 2,943 | 11% |

| Transfer to another agency | 2,726 | 1% | 2,263 | 1% | 463 | 17% |

| Runaway | 608 | 0% | 528 | 0% | 80 | 13% |

| Death of Child | 385 | 0% | 360 | 0% | 25 | 6% |

It is surprising that the number of foster care exits due to emancipation or “aging out” of foster care fell only slightly, to 20,010 in FY 2020 from 20,445 in FY 2019, making emancipations a slightly higher percentage of exits in FY 2020–8.9 percent, vs. 8.2 percent in FY 2019. There has been widespread concern about youth aging out of foster care during the pandemic, and a federal moratorium on emancipations was passed after the fiscal year ended. At least two jurisdictions, California and the District of Columbia, allowed youth to remain in care past their twenty-first birthdays due to the pandemic. It is surprising that this policy in California, with 50,737 youth in care or 12.45 percent of the nation’s foster youth on September 30, 2020, did not result in a bigger drop in emancipation exits nationwide. California’s foster care extension took effect on April 17, 2020 through an executive order by the Governor and was later expanded through the state budget to June 30, 2021. And indeed, data from California via the Child Welfare Indicators Project show that the number of youth exiting through emancipation dropped by over 1,000 from 3,618 in FY 2019 to 2,615 in FY 2020. Since total emancipation exits dropped by only 435 nationwide, it appears that the number of youth exiting care through emancipation outside of California actually increased. This raises concern about the fate of those young people who aged out of care during the first seven months of the pandemic.

In December 2020 (after the Fiscal Year was already over), Congress passed the Supporting Foster Youth and Families Through the Pandemic Act (P.L. 116-260), which banned states from allowing a child to age out of foster care before October 1, 2021, allowed youth who have exited foster care during the pandemic to return to care and added federal funding for this purpose. But this occurred after the end of FY 2020 so it did not affect the numbers for that year. Moreover, The Imprint reported in March 2021 that many states were not offering youth the option to stay in care despite the legislation, raising fears that the number of emancipations in FY 2021 may not have been much lower than the number for FY 2020.

Among the other data included in the AFCARS report, terminations of parental rights decreased by 11.2 percent in FY 2020. This is not surprising given the court shutdowns and delays. Perhaps this decline in TPR’s explains why the number of children waiting to be adopted actually decreased from 123,809 to 117,470, contrary to what might be expected from the decrease in adoptions.

It is disconcerting that some child welfare leaders and media outlets are portraying the reductions in foster care caseloads during FY 2020 as a beneficial byproduct of the pandemic. Despite the fact that maltreatment reports dropped by about half after the pandemic struck, Commissioner David Hansell of New York City’s Administration for Children’s Services told the Imprint that “It was just as likely that the pandemic was ‘a very positive thing’ for children, who were able to spend more time with their parents.” Based on an interview with Connecticut’s Commissioner of Children and Families, an NBC reporter stated that ‘With the pandemic, the last two years have been difficult, but something positive has also happened during that time span. Today, there are fewer kids in foster care in Connecticut.”

Even In normal times, I take issue with using reductions in foster care numbers as an indicator of success. Certainly if foster care placements can be reduced without increasing harm to children, that is a good thing. But in the wake of the pandemic, we know that many children were isolated from adults other than their parents due to stay-at-home orders and school closures, and we have seen a drastic decline in calls to child abuse hotlines. Thus, it is likely that some children were left in unsafe situations. Moreover, the pandemic caused increased stress to many parents, which may have led to increased maltreatment, as some evidence is beginning to show. So when Oregon’s Deputy Director of Child Welfare Practice and Programming told a reporter that “Even though we had fewer calls, the right calls were coming in and we got to the children who needed us,” one wonders how she knows that was the case, and whether her statement reflects wishful thinking rather than actual information.**

There have been many predictions of an onslaught of calls to child protective services hotlines once children returned to school. And indeed, there have been reports of a surge of calls after schools re-opened in Arizona, Kentucky, upstate New York, and other places, but we will have to wait another year for the national data on CPS reports and foster care entries after pandemic closures lifted.

The FY 2020 data on foster care around the country provided in the long-awaited AFCARS report contains few surprises. As expected by many, foster care entries and exits both fell in the first year of the pandemic. Since entries fell more than exits, the total number of children in foster care fell by over four percent. These numbers raise concerns regarding children who remained in unsafe homes and those who stayed in foster care too long due to agency and court delays. The one surprise was a concerning one: the lack of a major pandemic impact on the number of youth aging out of care. The second pandemic fiscal year has already come and gone, but it will be another year before we can get a national picture of how child welfare systems adjusted to operating during a pandemic.

*Our percentages are slightly different from those in the federal Trends report because the Children’s Bureau calculated their percentages based on numbers rounded to the nearest thousand.

*There is evidence that maltreatment referrals from school personnel are less likely to be substantiated than reports from other groups, and this may reflect their tendency to make referrals that do not rise to the level of maltreatment, perhaps out of concern to comply with mandatory reporting requirements. Data from the first three months of the pandemic shared in a webinar showed that referrals which had a lower risk score (measured by predictive analytics) tended to drop off more than referrals with a higher risk score. However as I pointed out in an earlier post, that low-risk referrals dropped off more does not mean that high-risk referrals were not lost as well.