Family resource centers, also called family support centers or family success centers, are becoming the prevention program of choice for child welfare agencies around the country. These neighborhood-based centers are being touted as America’s best hope for preventing child maltreatment before it occurs. But the proponents of these centers have been a little too eager in their claims that these programs are supported by research. Two studies recently released to great fanfare do not stand up to close examination. The sites chosen appear to have been chosen for their potential to support the desired conclusion, the evaluations do not convincingly adjust for confounding factors (a major misstatement was made in one of the studies regarding the implementation date of a possibly confounding policy), and the studies are rife with methodological problems related to the measure of success and the attribution of outcomes to the programs.

According to the Child Welfare Information Gateway, family resource centers are “community-based or school-based, flexible, family-focused, and culturally sensitive hubs of support and resources that provide programs and targeted services based on the needs and interests of families.” These centers are known by different names around the country, including Family Centers, Family Success Centers, Family Support Centers, and Parent Child Centers. Services provided often include parenting support, access to resources, child development activities, and parent leadership development.

Family resource centers (FRC’s) are being heavily promoted by child welfare agency leaders, as well as influential private actors such as Casey Family Programs as “less punitive, more open-ended, flexible and voluntary venues where vulnerable families can connect to services, particularly in the communities sending the most children to foster care,” as a recent article in The Imprint put it. FRC’s are gaining increased support around the country. New York City recently announced that it would expand from three to thirty Family Enrichment Centers. In October 2021, the District of Columbia opened ten new Family Success Centers in 2021, under its “Families First DC” initiative. Texas has recently announced that it is investing $1 million to create an unspecified number of Family Resource Centers, and has announced the first five grantees. Many other jurisdictions, such as New Jersey, Vermont, and Allegheny County Pennsylvania, have been operating FRC’s for years. A national membership organization called the National Family Support Network (NFSN) represents and promotes these centers.

Two recent studies have drawn press attention with reports that two family resource centers have been very successful preventing child maltreatment and as a result are saving money for taxpayers. The studies were carried out by a Denver nonprofit called the OMNI Institute, “in partnership with” the NFSN and Casey Family Programs. The researchers report that they identified the two programs by contacting NFSN members and reviewing existing evaluations of FRCs “to identify potential opportunities that could serve as return on investment case studies.”

One of the two programs studied was the Community Partnership Family Resource Center (CPFRP) in Teller County, Colorado, a rural county in central Colorado with a population of approximately 25,000 that is almost all White. As described in their report, the researchers wanted to explore the impact of two new programs that the center implemented in 2014 and 2016, that they hypothesized might have the effect of preventing child abuse and neglect in the county. One of these programs was Colorado Community Response, a voluntary program for parents who were reported for abuse or neglect but were either screened out at the hotline level or investigated but received no child welfare services. A second program, Family Development Services, was a voluntary primary prevention program helping struggling families set goals and connect to resources. The researchers claim that the creation of Colorado Community Response and increased funding for Family Development Services offered “a potential opportunity to examine the Return on Investment for CPFRC to the child welfare system, by comparing child maltreatment outcomes prior to and after the establishment of these new practices.” They decided to use the number of maltreatment allegations that were “substantiated” (or found to be true upon investigation) as their outcome of interest.

In designing their study, the researchers sought to identify other changes that might also affect levels of child maltreatment in order to avoid confounding effects. They learned that Colorado had implemented a “differential response” model in 2013, which was a two-track model for addressing allegations of abuse or neglect. Allegations that are viewed as less serious are assigned to the alternative response track and usually do not receive a substantiation, or finding of abuse or neglect. Obviously, the change to differential response might dramatically affect the number of substantiations. The researchers identified several other policy changes and events that might have affected substantiations, such as the establishment of a statewide child abuse hotline and the inception of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the report, they decided to use 2015 is the baseline year because “neither Colorado Community Response nor Family Development Services programming were available to the whole CPFRC population, but the statewide child abuse hotline and differential response models were in place.” They chose 2018 as the comparison year because it was the only year that both Colorado Community Response (CCR) and Family Development Services were fully implemented with no other major system-wide changes in place, and before a change in CCR eligibility requirements and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

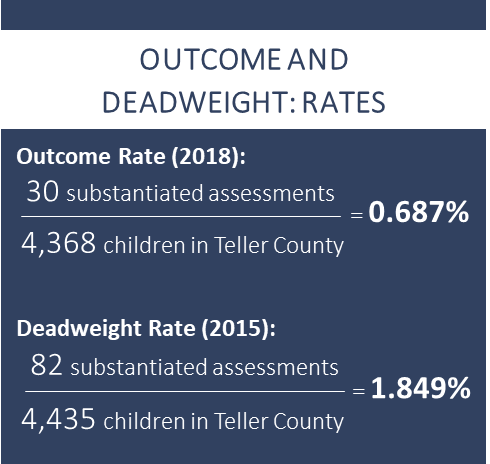

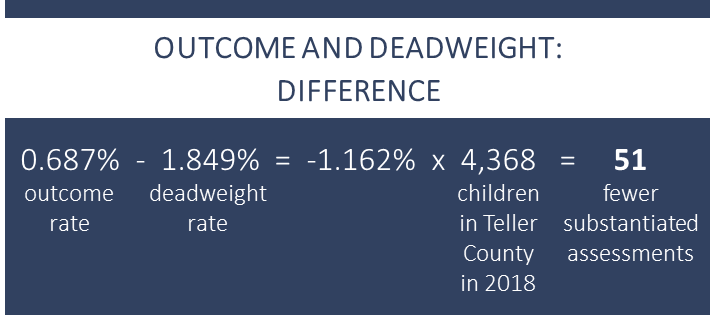

Using data provided by the state on its online dashboard, the OMNI researchers found that there were 82 substantiated assessments in 2015 and only 30 in 2018. To adjust for population changes they divided each number by the number of children in the County at the time, producing what they called an “outcome weight” for 2015 and a “deadweight rate” for 2018, as described in the first graphic below. Subtracting the deadweight rate from the outcome weight and multiplying by the child population in 2018, the researchers came up with a reduction of 51 fewer substantiated assessments in 2018, as illustrated in the second graphic. (The adjustment made little difference; simply subtracting the 30 from 82 resulted in a reduction of 52 substantiated assessments.) This impressive drop in substantiated cases translates to a “62.84 percent reduction in substantiated assessments from 2015 to 2018.”

Family Resource Center to the Child Welfare System. Available from https://childwelfaremonitor.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/8b78c-communitypartnershipfamilyresourcecenterchildwelfarereturnoninvestmenttechnicalappendix.pdf.

The researchers used the estimated number of children served by CPFRC during 2018 (1,444) relative to the estimated number of children at risk for maltreatment based on income-to-needs (ITN) ratio (1,479)* and age (1,272), to decide how much of the change in substantiations to attribute to the program. The result was an “attribution estimate of 98 percent based on the ITN ratio and 114 percent based on age. Combining these estimates, the researchers decided to attribute the entire reduction in substantiated cases to CPFRC.

Finally, the researchers calculated a return on investment using total child welfare expenditures in 2018 divided by the number of substantiated assessments in that year, resulting in a total cost of $49,026 per substantiated investment. Multiplying that figure by 51, they concluded that the reduction of 51 substantiated assessments, (of which 100 percent were attributed to the program) saved the Teller County child welfare system $2,500,326 in 2018 compared to 2015. Dividing this total by $856,194, they came up with a “Return on Investment” of $2.92 for every dollar spent on the program.

There are many serious problems with this analysis. The choice of substantiations as an indicator of victimization is problematic because of the large body of literature illustrating the difficulty of determining if a child has been maltreated and the absence of differences in future outcomes between children with substantiated vs. unsubstantiated allegations. Allegations (or referrals) seem to be a more meaningful measure of abuse or neglect. Using data from two years without looking at the numbers for the years in-between is also problematic, as the researchers themselves admit. In their discussion of the weaknesses of the study, they acknowledge that using only two years, without the years in between, is not ideal because it provides a less robust understanding of changes in child maltreatment as well as making its estimates more susceptible to influence by other system-level factors.

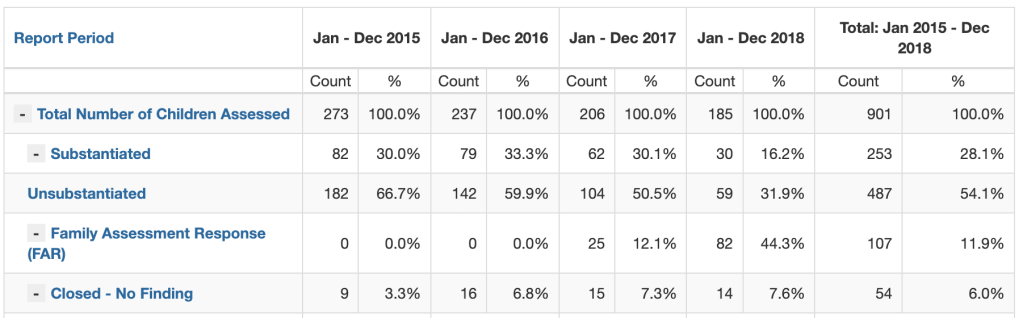

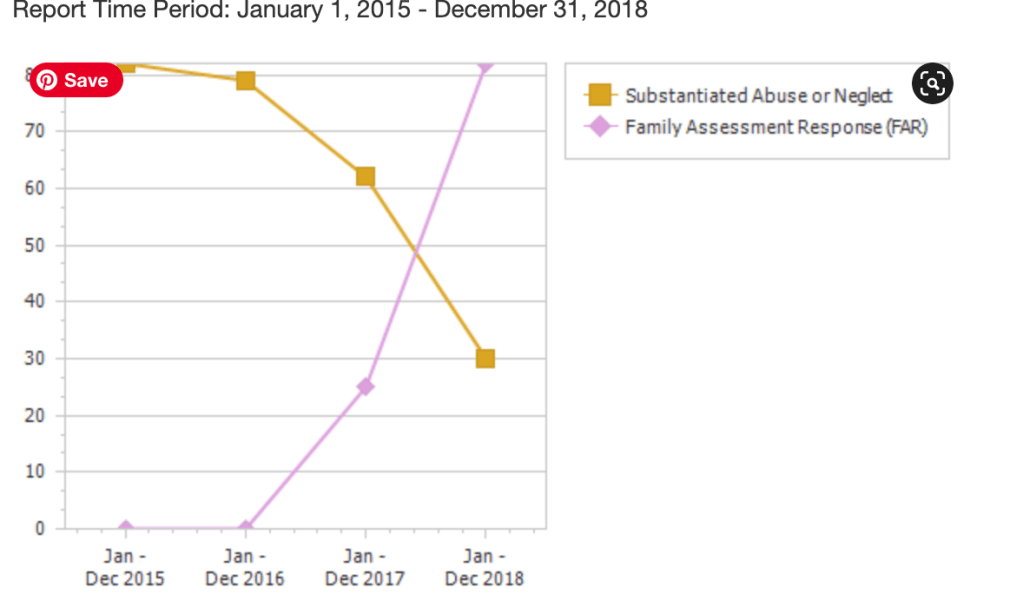

But there is a much worse –indeed fatal–problem with the two years chosen. The researchers claim that they chose 2015 because Differential Response was already in effect in in that year, having been implemented in 2013. But going to Colorado’s “Community Performance Center” (data dashboard) as helpfully directed by a footnote, one quickly learns that no children were assigned to Family Assessment Response (the option that does not result in substantiation) in Teller County in 2015, as shown in Table One below. In 2018, 82 children, or 44.3 percent of all children assessed, were assigned to Family Assessment Response. So an unknown part of the decrease in the number of children substantiated could have been due to the rollout of Differential Response.

Table One

If there was any doubt that the advent of Differential Response may be related to the drop in substantiated assessments, one only has to look at Figure One below. It is hard to figure out how the researchers missed this graphic, which is prominently displayed on the relevant page of the data dashboard, and shows how substantiations fell between 2016 and 2018 as the number of children assessed through FAR increased. This is a bizarre error, considering that the researchers specifically cited the prior rollout of differential response as a reason for choosing 2015 as the baseline year for the study.

Another problem is the method the researchers used to attribute all of the “reduction” in cases to the program. First, the authors provide no explanation of the estimate that 1,444 children received services at CPFRC. We assume this includes every child who ever walked into the center, but we just do not know, since the researchers do not define it. We have no idea of the quantity of services received by each child. We don’t even know if this is an unduplicated count. Moreover, this conclusion simply violates common sense. On the face of it, how could one assume that one family support center caused the entire reduction in child maltreatment substantiations in a county? It just beggars belief.

The second study by OMNI focused on the Westminster Family Resource Center (WFRC), which serves a mostly-Latino population in Orange County, California. WFRC provides a variety of services, including information and referral, family support, case management, counseling, after school programs, domestic violence support, parenting classes, and “family reunification family fun activities.” WFRC belongs to a network of 15 Family Resource Centers known as Families and Communities Together (FaCT). The researchers report that In conducting the study OMNI took advantage of a pre-existing evaluation of all the centers in the FaCT network, which was conducted by Casey Family Programs, Orange County Social Services Agency, another nonprofit and a consulting firm. OMNI reports that “After consultation with the evaluation team and a review of the demographic profile of the areas served by FRCs within Orange County as a whole, OMNI identified Westminster Family Resource Center (WFRC) as a strong option for this project.” (The larger study is listed as “forthcoming” from Casey Family Programs in the references to the OMNI report.)

Unlike the Teller County report, the Orange County report compares outcomes across geographic areas rather than two time periods. The researchers defined WFRC’s service area as the census tracts where at least one percent of the population was served by WFRC. They matched 12 census tracts in Los Angeles County to the area served by WFRP based on ten “community level indicators related to child maltreatment,” such as the percentage of families in poverty and the unemployment rate; the other indicators were not listed.

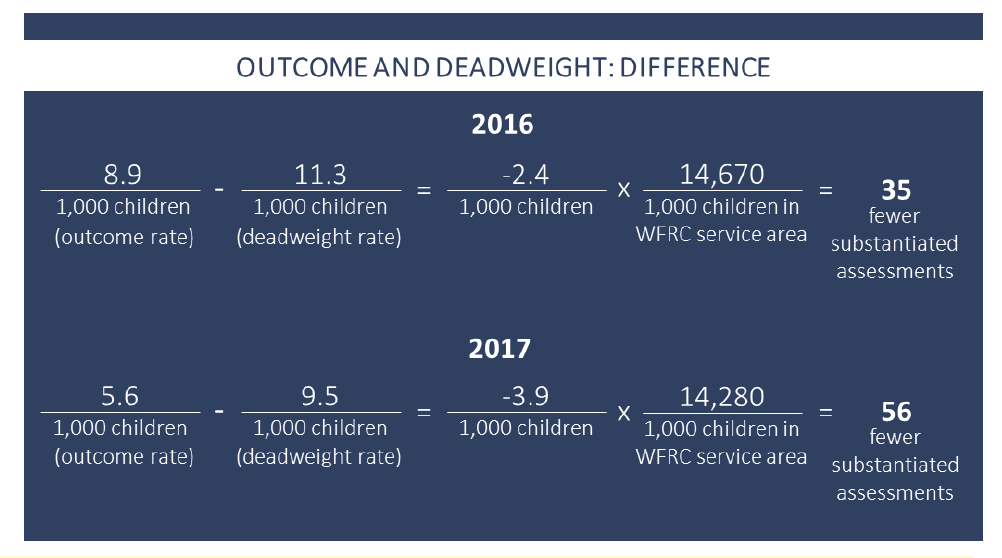

Using data from the pre-existing evaluation, the researchers subtracted the substantiation rate (number of substantiated children per 1000) in the WFRC areas from the substantiation rate in the matched areas for 2016 and 2017, the most recent years for which data were available, and then multiplied the difference by the number of children in the WFRC service area. The calculation is shown in the attached graphic, which incorrectly divides the number of children in the service area by 1,000. This calculation produced an estimate of 35 fewer substantiated assessments in 2016 and 56 fewer substantiated assessments in 2017. Unlike with the Teller County study, a reader cannot check the underlying data because it comes from an as yet unpublished study. Admitting that there are no guidelines for attributing results to a program in a “quasi-experimental evaluation” using community-level indicators, the researchers rather randomly decided to attribute 50 percent of the difference in substantiated assessments to the program.

Family Resource Center to theChild Welfare System, Westminster Family Resource Center, Orange

County, CA. Available from https://childwelfaremonitor.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/7845f-westminsterfamilyresourcecenterchildwelfarereturnoninvestmenttechnicalappendix.pdf

Note that the the equations are incorrect. The number of children in the service area was not divided by 1,000.

As in the Teller County study, the researchers went on to calculate a return on investment for WFRC. Although they did not explain their methodology for doing so, it appears they used the same approach of dividing child welfare costs for each year by the number of substantiated assessments for that year to come up with an estimated cost per substantiated assessment in California, adjusting for inflation, and finally subtracting the estimated costs of WFRC. By this method, they arrived at a return on investment of $2.80 in 2016 and $4.51 in 2017, which they averaged to get a total return on investment of $3.65 per dollar spent on the program.

The use of substantiation rates as an indicator of success is as problematic as in the Teller County study. As I have mentioned, substantiation does not equal victimization but instead reflects the agency’s performance in determining whether maltreatment really happened. Using substantiation as an indicator of maltreatment could introduce bias if one of these counties substantiated allegations at a higher proportion of cases than the other, as discussed below.

While there is no mistake as glaring as the Teller County team’s erroneous assumption that differential response had already been implemented in the study’s baseline year, the possibility of significant confounding effects does exist–in this case between places rather than times. California has a county-run child welfare system and the writers do not discuss any policy or practice differences that may exist between Los Angeles County and Orange County and how they might affect the differences in substantiation rate between the two counties. And indeed, data from the Child Welfare Indicators Project at Berkeley shows that Los Angeles County does substantiate a higher proportion of allegations than does Orange County. Of all the children with allegations in 2016 and 2017, 15.7 and 14.7 percent had substantiations in Orange County, versus about 18 percent in Los Angeles County both years. In addition, the fact that the reduction in substantiated assessments, and therefore the estimated cost savings due to the program, varied so much between 2016 and 2017 is already concerning and suggest that the impact found depends upon the year, and could be vastly different if another year were chosen.

The attribution of 50 percent of the difference in substantiations between the two counties to the WFRP has no basis in fact or social science. The researchers did not attempt the kind of calculation reported for Teller County (however problematic) in which they compared the number of children served to the number of children who might be at risk of maltreatment. They indicate that WFP served 1.77 percent of households in its service area as defined by the researchers, and we have no idea how that compares to the number of households where children are at risk of maltreatment.

Looking at the Teller County and Orange County studies together, the choice of these two specific programs out of all the over 3,000 FRC’s represented by NFSN (and the choice of only one out of 15 programs evaluated in Orange County) raises the possibility that the researchers cherry-picked programs to achieve the desired results. In fact, the researchers report that that is exactly what they did! One of the criteria they reported using to select their ultimate sites was that “there were available data demonstrating a plausible connection between FRC services and child welfare system outcomes;” another was that “[t]here were available quantitative data demonstrating that the child welfare system has benefited (e.g., through reductions in the incidence of child abuse/neglect).” The researchers also claim that they were looking for sites representing “demographically different communities,” and I suppose they achieved that with their two sites with mostly White and Latino clientele; but they seem to have been unable to find a suitably promising site with a predominantly Black clientele.

Clearly it is not easy to evaluate programs without random assignment to a treatment and control group, or at least a comparison group that is matched individually to a group of participants. It is also difficult to evaluate a program where each participant gets a different package of services, with some receiving as little as one visit to the center. There is ample reason to doubt that Family Resource Centers will have a large impact on the most serious cases of child abuse and neglect because the parents who use these centers tend to be those who are already open to seeking help, learning new parenting tools, and working toward change. It seems likely that the parents of the most vulnerable children are often the ones who are not willing to seek the kind of help that Family Resource Centers provide. Chronically neglectful parents may lack energy and motivation to go to a Family Resource Center; chronically abusive families are likely to want to avoid letting other adults set eyes on their children. That is why jurisdictions that are really serious about prevention have chosen to adopt more targeted strategies. For example, Allegheny County Pennsylvania, which has a network of 27 Family Resource Centers and was a pioneer in this effort, knew they had to do more for families with more intense needs. They created a three-tier model called Hello Baby, in which families are placed into tiers based on their needs. They are reaching out to all families, and they are referring those in the middle tier to county’s FRC’s. For the families with the greatest needs, a more intensive option is being offered.

A recurrent theme of this blog has been the use of flawed research to promote the programs that the promoters want to support, most recently in my post about race-blind removals. Using flawed research to support programs results in misperceptions by the public and its representatives and in turn to bad policy decisions. One does not have to look beyond Teller County for an example “Child abuse reports have declined dramatically locally due to a partnership between a key Teller government agency and a nonprofit organization,” trumpeted a local paper based on the press release from OMNI. In the article, the DHS Director Kim Mauthe was reported as saying that “the findings of the report are good news for the county. “It’s exciting because the calls we did receive through our child abuse hotline show that we had a decrease of child abuse by 57 percent, which is huge….” It is not clear what would be more disturbing: that Mauthe really believed this program had reduced child maltreatment (not “abuse” as she described it) by 57 percent, knowing that the study period included her county’s adoption of differential response, or that she was cynically misrepresenting the study results to the media. The report was presented at a meeting of county commissioners, who applauded Ms. Mauthe. They now presumably think that child maltreatment is on its way to disappearing, and if anything more is needed it would be to add more funding to the Family Resource Center–not necessarily the best approach if they want to reach the families with the most intense needs.

It is not surprising that this flawed research was funded and promoted by Casey Family Programs, a wealthy and powerful non-profit that has played an outsized role in child welfare in recent decades, funding advocacy-oriented research, providing free consultation to states, and even helping the government hire people who support its views. One of CFP’s goals is to “safely reduce the need for foster care in the United States by 50 percent,” a goal that is incidentally meaningless without a beginning and ending date. Most recently, CFP has publicized the faulty data on race-blind removals that I discussed in a recent post.

Family resource centers can be a great addition to a neighborhood, providing connections to needed programs and services for needy families. But two recent studies that claim to show that these centers reduce child maltreatment and thereby save money to taxpayers are too flawed to provide any meaningful evidence that they indeed have this effect. Any continuing publicity these studies receive may lead unsuspecting public officials to invest in family resource centers at the expense of other programs that may be more promising in preventing child maltreatment.