Officials of New Jersey’s Department of Children and Families (DCF) are congratulating themselves on what they call the decline of child abuse and neglect in their state and attributing this ostensible decline to their department’s preventive services. The number of reports of child child maltreatment has actually increased over this period. DCF’s claims are based on a decline in the number of children with substantiated reports–a number which reflects DCF policy and practice much more than it reflects actual abuse and neglect. Whether agency officials are ignorant or attempting to manipulate the data for naive readers, this is no way to keep the public informed about how well New Jersey is protecting its children.

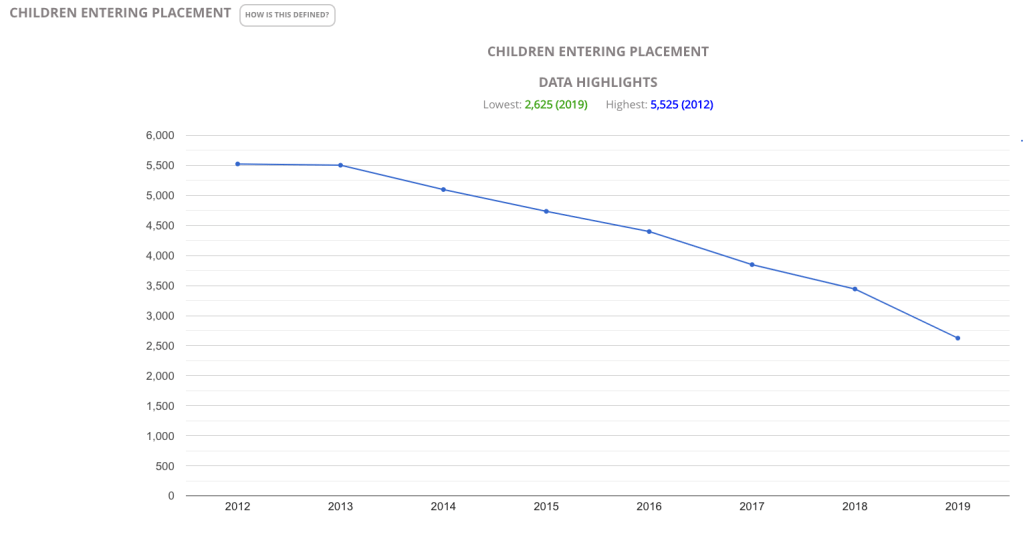

Two DCF officials, Laura Jamey, Director of the Division of Child Protection and Permanency and Sanford Starr, Director of the Division of Family and Community Partnerships, say they have some good news for New Jerseyans. They announce it in an op-ed titled “Maltreatment of NJ kids is decreasing. Here’s wow [sic] we’re preventing it,” which was published in the Asbury Park Press. “By using evidenced-based [sic] prevention strategies and practically addressing families’ needs, we’re happy to report that over the past decade, there has been a steady decline in the number of confirmed cases of child abuse and neglect in our state. In 2016, there were more than 8,000 substantiated and established cases of Child Abuse and Neglect in New Jersey. Last year, that number was only 2,641.”

Wow! sounds impressive, right? But it turns out the authors took as much care with the substance of their commentary as with their capitalization and spelling. That much is clear to anyone who bothers to look at the data that New Jersey shares with the federal government through the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) and which the federal Children’s Bureau shares through its annual Child Maltreatment reports. The data for 2023 have not yet been published by the Bureau, but the figures below represent what New Jersey reported for Federal Fiscal Years (FFY) 2016 to 2022, which ended on September 30, 2022.

| Federal Fiscal Year | Referrals | Children Receiving an Investigation or Alternative response | Children receiving a “substantiated” disposition/percent of referrals |

| 2016 | 56,014 | 73,889 | 8,264 (11.2%) |

| 2017 | 57,026 | 74,393 | 6,614 (11.6%) |

| 2018 | 59, 428 | 77,661 | 6,008 (10.1%) |

| 2019 | 60,934 | 78,741 | 5,132 (8.4%) |

| 2020 | 52,853 | 70,179 | 3,655 (6.9%) |

| 2021 | 48,781 | 66,321 | 3,188 (6.5%) |

| 2022 | 57,068 | 74,766 | 3,146 (5.5%) |

Jamey and Starr cited only the number of substantiated cases of maltreatment. But that figure has meaning only in the context of two figures that represent earlier steps in the process, which are always discussed first in the Child Maltreatment reports. “Referrals” is the child welfare system’s term for reports to the state child protective services hotline. As you can see, those reports increased slightly in New Jersey from 56,014 in FFY2016 to 60,934 in FFY2019. There was a significant drop in referrals during the COVID pandemic in FFY2020 and FFY2021, and then a rebound to 57,068 in FFY 2022, just slightly higher than the number in 2016.

The number of children who were the subject of an investigation also dipped during COVID (in response to the drop in referrals) and bounced back up to a level that was slightly higher than that of 2016. But the number of cases that received a disposition of “substantiated” (which means an investigation concluded that a preponderance of the evidence indicated that abuse and neglect occurred) fell every year, with especially large drops in 2017 and during the COVID pandemic. And according to Jamey and Staff, that number fell even further to 2,641 in 2023, which means the number of children with substantiated referrals had dropped by 68 percent since FFY2016. And the number of children receiving a substantiated disposition as a percent of all referrals fell by half–from 11.2 percent to 5.5 percent, in that period.

So what explains this large drop in children with substantiated dispositions during a period of nine years? In its commentary in Child Maltreatment 2017 (CM2017), New Jersey attributed the one-year drop in children with substantiated dispositions from FFY 2016 to FFY2017 to a revised disposition model it adopted in April 2013.1 But after FFY2017, DCF provided no explanations other than regularly repeating its statement in 2018 that “the decrease in the number of substantiated victims “remains consistent with prior years and shows a continued trend in the decrease of victimization rates.” In CM2022, DCF simply acknowledged without explaining that “[d]espite the number of CPS referrals increasing from FFY 2021 to FFY 2022, the number of child victims continues to decrease. The rate in which New Jersey substantiated reports also decreased from FFY 2021 to FFY 2022.”

Research suggests that substantiation decisions are not very accurate and that a report to the hotline predicts future maltreatment reports and developmental outcomes almost as well as a substantiated report.2 So it just does not seem plausible that child maltreatment could have dropped by over half while the number of reports increased. There is one possible explanation for this decline, which I raised in a 2021 blog. New Jersey is one of many states that is increasingly using a practice called “kinship diversion.” Kinship diversion occurs when social workers determine that a child cannot remain safely with the parents or guardians. Instead of taking custody of a child, the agency facilitates placing the child with a relative or family friend. If this occurs in the context of an investigation, kinship diversion may result in a finding of “unsubstantiated” (or in New Jersey, “unfounded” or “not established”) even when abuse or neglect has occurred, on the grounds that the child is now safe with the relative. We have no idea how widespread kinship diversion is in New Jersey or how often it results in an “unfounded” or “not established” finding. However, the system of informal kinship care created by kinship diversion has been called America’s hidden foster care system and nationwide it appears to dwarf the provision of kinship care within the foster care system.

There is no way of knowing how much, if any, of the drop in child maltreatment substantiations is accounted for by kinship diversion. If diversion accounts for a substantial portion of the drop, that points to serious problems with the practice. It means not only that DCF is undercounting incidents of child abuse or neglect but also that a parent who committed serious maltreatment would not show up as having a substantiated report, possibly affecting decisions on future allegations against that parent. I described some of the other problems with kinship diversion, such as the lack of support for the child and relatives, the possibility that the caregiver will return the child to the an unsafe home, the possible placement of children with inadequately-vetted relatives, and the lack of due process and services for the parents, in another post.

Despite their lack of explanation in their annual commentaries designed for federal employees and child welfare specialists to read, DCF officials have offered the public an optimistic explanation for the drop in maltreatment substantiations. “We’ve worked to transform New Jersey’s child welfare system to support and strengthen families who are struggling to meet their basic needs rather than separating them. A family unable to provide clean clothes may need a supportive neighbor who can offer a ride to the local laundromat. A family struggling to put food on the table may need to be connected with a local food bank.” We have already shown that this decline does not indicate a decline in actual maltreatment, but this attempt to tie it to simple casework like finding a family a ride to a laundromat is simply not believable.

The problem is not just an op-ed that few will read. As quoted in NJ Spotlight News, the Commissioner of DCF told a legislative committee that “Working together, we have achieved so much for New Jersey’s families, including the lowest rate of family separations in the country, one of the lowest rates of child maltreatment and repeat maltreatment in the country.” This was quoted as part of a congratulatory article about how New Jersey has become a “national leader in child welfare.” it is unfortunate that this public media outlet simply echoed the Department’s rosy view, making no attempt to verify their claims by consulting the data.

The misuse of data by high officials of New Jersey’s child welfare agency raises an uncomfortable question. Is it really possible that these leaders believe that child maltreatment has declined by 68 percent since 2016? All I can say is that their statement reflects either ignorance or a cynical disregard for the truth. Neither of these options reflects well on the leadership’s moral or intellectual capacity to serve their state’s most vulnerable children and families.

Notes

- Before the new framework, New Jersey had only two investigation dispositions: unfounded and substantiated. The new model added two new dispositions: established and not established, which fall on a continuum between “substantiated” and “unfounded.” DCF explains that the cases that receive the “established” disposition are coded as “substantiated” in NCANDS, so it is possible that finding some children who would have been substantiated as “not established” instead contributed to the drop in substantiations. ↩︎

- Theodore Cross and Cecilia Casanueva, “Caseworker Judgments and Substantiation,” Child Maltreatment, 14, 1 (2009): 38-52; Desmond K. Runyan et al, “Describing Maltreatment: Do child protective services reports and research definitions agree?” Child Abuse and Neglect 29 (2005): 461-477; Brett Drake, “Unraveling ‘Unsubstantiated,’” Child Maltreatment, August 1996; and Amy M. Smith Slep and Richard E. Heyman, “Creating and Field-Testing Child Maltreatment Definitions: Improving the Reliability of Substantiation Determinations,” Child Maltreatment, 11, 3 (August 2006): 217-236. Brett Drake, Melissa Jonson-Reid, Ineke Wy and Silke Chung, “Substantiation and Recidivism,” Child Maltreatment 8,4 (2003): 248-260; Jon M. Hussey et al., “Defining maltreatment according to substantiation: Distinction without a difference?” Child Abuse and Neglect 29 (2005): 479-492; Patricia L. Kohl, Melissa Jonson-Reid, and Brett Drake, “Time to Leave Substantiation Behind: Findings from a National Probability Study,” Child Maltreatment, 14 (2009), 17-26; Jeffrey Leiter, Kristen A. Myers, and Matthew T. Zingraff, “Substantiated and unsubstantiated cases of child maltreatment: do their consequences differ?” Social Work Research 18 (1994): 67-82; and Diana J. English et al, “Causes and Consequences of the Substantiation Decision in Washington State Child Protective Services,” Children and Youth Services Review, 24, 11 (2002): 817-851. ↩︎