By Marie K. Cohen

As readers digest the report that follows, the content may cause significant discomfort stemming from painful, lived personal experiences and perspectives shaped by social constructs made implicit through centuries of white supremacy and structural oppression. Readers are invited to practice self-care while navigating this content and to consider reading the findings with a group to engage in collective reflection.

Tyrone Howard et al, Beyond Blind Removal: Color Consciousness and Anti-Racism in Los Angeles County Child Welfare. UCLA Pritzker Center for Strengthening Children and Families, March 2024, page 5.

For several years, and accelerating after the murder of George Floyd, concerns about the overrepresentation of Black children in child welfare compared to their share of the population have been a leading factor behind proposals to reform child welfare services. One reform proposal–known as “blind removal”–seemed blessedly simple: just hide the race and ethnicity of a child being considered for placement in foster care, and racial differences in child removal will disappear. Los Angeles County was one of the jurisdictions that decided to pilot this new approach, and an evaluation of this pilot was released last month. On first reading, the evaluation looks like evidence that the pilot failed to reduce disproportional Black representation in child welfare. On second reading, the weaknesses of the study come into focus, and it appears to be proof of nothing. On third reading, it becomes clear that the poor quality of the evaluation reflects the evaluators’ and agency’s response to a legislative mandate to pilot a program that they no longer supported because it was “color-blind,” as they proceeded in their plans to develop the “color-conscious” programs they preferred. Apparent from the beginning was that neither the sponsor, nor the agency, nor the researchers stopped to examine the data on blind removals provided in a TED Talk, nor did they consider the basic assumption behind this approach.

On July 13, 2021, the Los Angeles Board of Supervisors passed a motion requiring the Los Angeles Department of Child and Family Services (DCFS) to pilot the blind removal concept. The sponsor, Supervisor Holly Mitchell, was influenced by the publicity around an experiment in New York State suggesting that the simple process of hiding racial details about children reported to CPS had been successful in erasing much of the racial disproportionality in foster care placements. A TED talk by Jessica Pryce, the scholar who “discovered” the use of this procedure in Nassau County New York, has been viewed 1.37 million times. In that talk, Pryce presented, to thunderous applause, her finding that after five years of implementing blind removal, the proportion of children entering foster care who were Black plummeted from 57 percent to 21 percent. A post entitled The power of wishful thinking: the case of race-blind removals in child welfare showed that the numbers cited by Pryce were simply wrong. The Black percentage of children who were removed fluctuated from year to year during and after the implementation of blind removals, ending up higher in FY2020 than it was before implementation of the program. But the supporters of blind removal did not seem to have much interest in anything that would cast doubt on this apparently simple fix for the stubborn fact of racial disproportionality in child welfare.

The blind removal pilot evaluation

This month, the Pritzker Center quietly released its report on the Los Angeles pilot, Beyond Blind Removal: Color Consciousness and Anti-Racism in Los Angeles County Child Welfare. The pilot ran from August 2022 to August 2023 in two county offices, West Los Angeles and Compton-Carson. The blind removal process began after the office had investigated an allegation of maltreatment and determined that the removal of a child or children was the only safe alternative. The case was then referred to a panel of administrators in West LA, and to one administrator outside the supervisory line in Compton-Carson. In both offices, the case reviewers were given case details that left out all information that could signal race or ethnicity, including name, race, ethnicity, zip code, income, and school district. Cases were not referred for blind removal when “exigent” circumstances were present, which means there was “reasonable cause to believe that the child was in imminent danger of serious bodily injury (which includes sexual abuse).” In West LA, a “Coach Developer” presented the case to a team of case reviewers with the investigative social worker and supervisor present, and the case reviewers voted at the end of the meeting on the decision to remove the child. The decision would then be conveyed to the social worker and supervisor. In Compton-Carson, the final decision was made in the blind removal meeting between the social worker, supervisor and case reviewer.

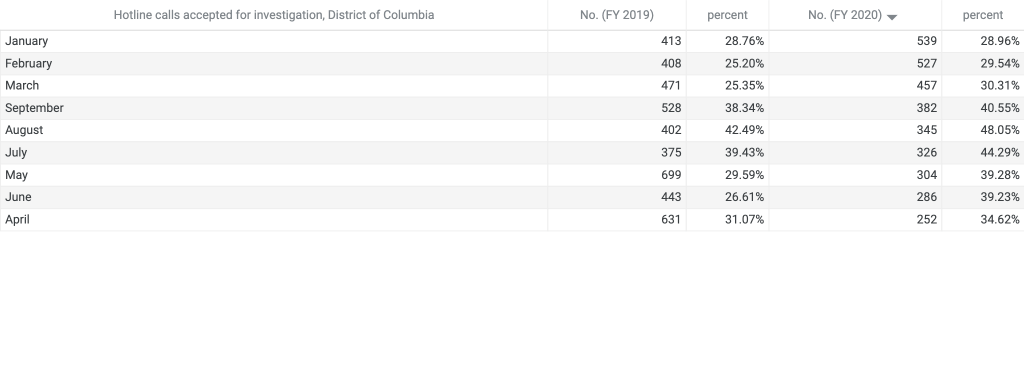

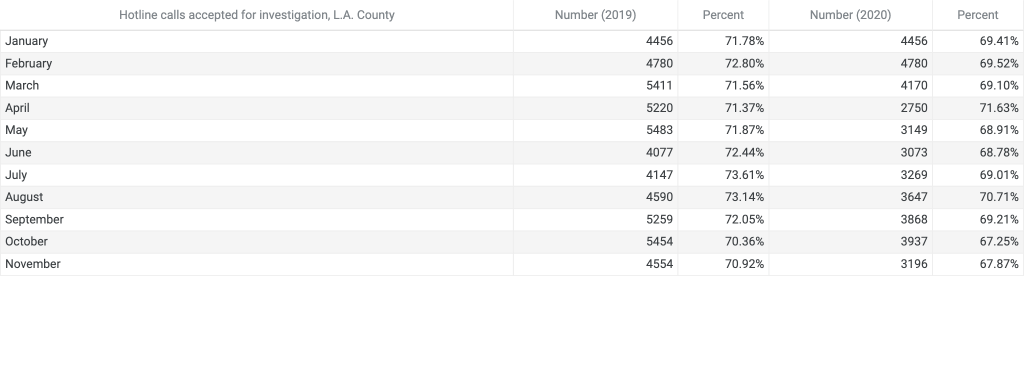

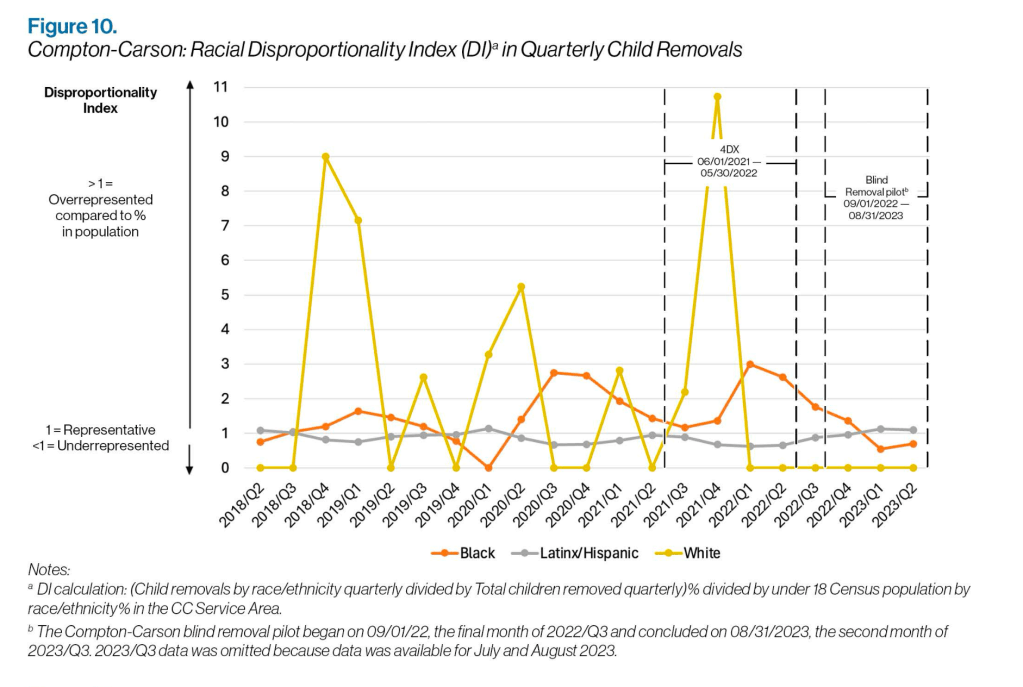

To assess the results of the pilot, the researchers used three separate administrative datasets from the Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) for hotline referrals, petitions filed, and cases that went through the blind removals process. The referral and removal datasets covered five years and three months from April 1, 2018 to June 30, 2023. The blind removal datasets covered the pilot period, from August 1, 2022 to July 31, 2023 in West LA, and September 1, 2022 to August 31, 2023 for Compton-Carson. It is strange and unfortunate that the referral and removal datasets did not cover the last month of the pilot in West LA and the last two months in Compton-Carson; we will see below that this omission caused a serious problem. For referrals and removals, the evaluators calculated a “Disproportionality Index” (DI), which depicts racial overrepresentation when greater than one, equal representation at one, and underrepresentation when less than one.

The researchers found that the total number of children who were removed from their families by each office trended downward during the study period but “racial disproportionality persisted with Black children overrepresented in removals in both offices and Latinx children overrepresented in the West LA office in most quarters.” They found very few non-exigent cases identified for removal in West LA went through the blind removal process. The office petitioned for the removal of 46 children over the period, of whom less than half (21 out of 46) received a blind removal review. The reasons these children were not referred for blind removal were not documented. The researchers report that the pilot was implemented with more fidelity in Compton-Carson, but they reported the results using different categories than they used for West LA, which made it hard to understand or compare the results of the two offices.*

Responses to a survey of workers and administrators provided little evidence of positive change. Social workers and supervisors largely perceived no change in how much they talked about race and ethnicity, the amount of support they received for talking about race and ethnicity and “managing their racial and ethnic biases in their work.” In addition, social workers and supervisors “mostly perceived no changes in how they conducted their daily work.” However, the researchers took pains to share the comments of the minority of employees that expressed positive views, reporting that “[s]ome interviewees came to understand that racial biases and stereotypes might unconsciously affect how decisions are made in the child welfare system.” And a fifth of social workers and supervisors “perceived greater engagement and support across key aspects of their work as defined in the Core Practice Model.”

But majorities of the staff interviewed expressed negative views about changes brought about by the pilot. Most important was the perception that the pilot worked against the prevailing approach of addressing disproportionality through race-conscious policies. As the authors put it, the blind removal pilot “was perceived as contradicting concerted efforts to address racial disproportionality in child removals by explicitly talking about race and increasingly building bridges with individuals and organizations in Black communities to support Black families.” The increased workload for administrative staff was a negative outcome, mentioned as a “source of frustration” by the authors.

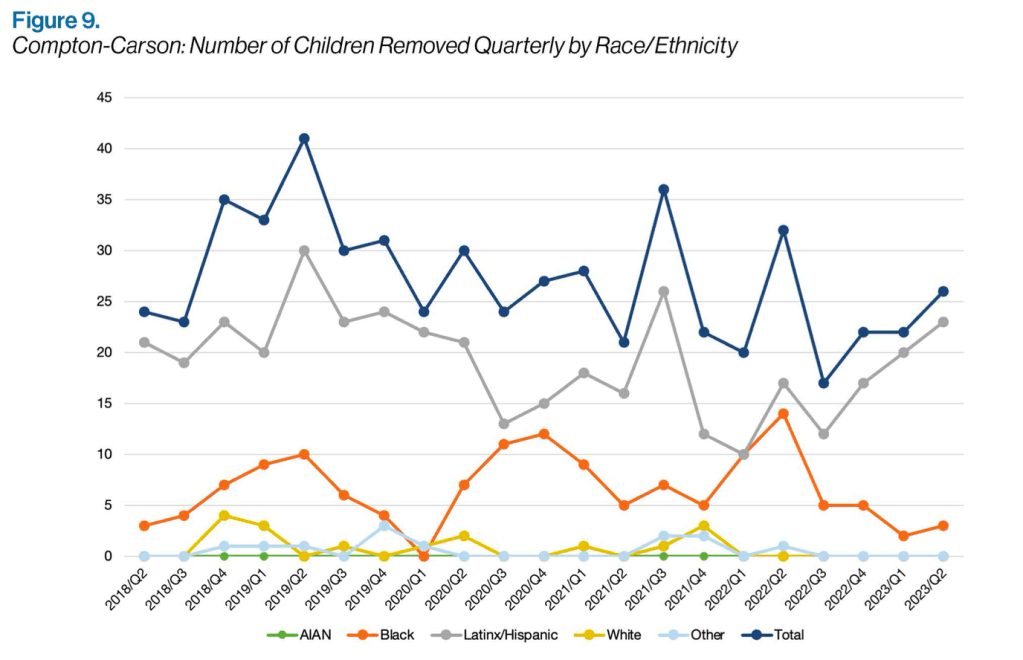

A sloppy, poorly-planned and badly-documented study

While it would not be surprising if the pilot was not the cure that its sponsors hoped for, the sloppy research design and presentation make it difficult to accept the results as proof of the failure or success of blind removal in achieving its goal in reducing disproportional removals of Black children. The lack of a comparison site was a big problem. One cannot compare trends over time and assume that nothing changed other than the pilot. The two pilot sites chosen were far from ideal. The West LA office has both a small caseload and a very small proportion of Black children in the population served–only 5.9 percent. The authors report that there were only 46 children removed during the entire pilot, only 21 of whom went through the blind removal process. The total number of Black children removed per quarter, as shown in Figure 4 below, ranged from 0 to what looks like six. Compton-Carson had three times as many cases as West LA. However, 81 percent of the service area population was Latino, and only 17 percent was Black. In the Compton-Carson office, the number of Black children removed was five or less in the last four quarters and the bulk of the children removed were Hispanic. The researchers also assessed Hispanic disproportionality, but it was almost nonexistent at Compton-Carson. Almost all of their discussion of disproportionality relates to Black children, so one might expect them to choose two districts with enough Black children to provide meaningful numbers of removals.

Even more problematic is the way the data were grouped for display and analysis, as shown in Figures 4 for West LA and Figures 9 and 10 for Compton-Carson. The researchers pooled their data for each calendar quarter despite the fact that in both sites, the pilot started and ended in the middle of a quarter. To make matters worse, data for the final month of the West LA pilot and the final two months of the Compton-Carson pilot are not provided because data were not available for the remaining one or two months–as mentioned above. So the reader cannot see the actual numbers of removals for the pilot period at either site; in only two of the four quarters shown was the plot was operational throughout the quarter.

The confounding of the effects of different interventions is another problem with the study design. This one cannot be blamed on the researchers, who warned that it would be a problem, as discussed below. Figure 9 shows that there was a decrease in the proportion of Black children removed in Compton-Carson starting in the second quarter of 2022, and a concurrent increase in the number of Hispanic children who were removed. This trend began before the blind removal pilot started but after the commencement of 4DX, another initiative to reduce disproportionality that was implemented in January 2021. Figure 10 shows the consequent decline in the Black DR, which falls below one in the first half of 2023, meaning that Black children were underrepresented in that period. The researchers conclude that the “decline cannot be attributed to 4DX because the intervention was not evaluated, nor can it be attributed to blind removal because this intervention was confounded by 4DX and other interventions meant to serve Black families more effectively, such as the Eliminating Racial Disparities and Disproportionality (ERDD) roundtables, and interventions designed to improve assessment of safety versus risk.”**

Missing information is also a problem. It would be impossible to assess the effect of the blind removal process without knowing how often the panel or individual reviewing the cases reversed the decision to remove a child, and whether there was any pattern in terms of race and ethnicity. The authors report that of the 21 children who were referred for blind removal in West LA, the panel agreed with the decision to remove all but two of the children. DCFS reported that those children had situations that “stabilized” presumably between the initial removal decision and the meeting, but the numbers are too small to make any general conclusions. In any case, there wre few reversals of the initial decision, and it appears that these reversals did not relate to race but to changes in the child’s situation. In Compton-Carson, the researchers did not even report on how often the initial removal decision was reversed in the blind removal meeting.

It is also odd that the authors devoted so much of their analysis to topics and periods outside of the one-year blind removal pilots. Much of the text and graphics is devoted to analysis of referrals (not addressed by the pilot), and they usually refer to the entire five-and-a-quarter-year period with little mention of what happened during the pilot. Much of the analysis simply documents the disproportionality in referrals and foster care placements throughout the period–something that really does not need more documentation and was not the reason for funding the pilot. Concentrating on the full period also allowed the writers to disregard the effect of the pilot. In the most flagrant example, the authors state that “Further, while overall child removals decreased in the Compton-Carson office, Black children were disproportionately represented in removals by the office during most quarters for which data were analyzed with a very slight upward trend collectively.” Clearly, the quarters during which the pilot was implemented show a downward trend. The authors are probably right that this proves nothing about blind removals, but this presentation gives the impression that they wanted to avoid saying anything that could be quoted by those wanting to demonstrate the pilot’s success.

A pilot that was doomed to fail?

The report’s section on “Timeline and Related Events” provides clues to the origins of the problems with the pilot’s design. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder and the subsequent demonstrations, the authors report that “child welfare systems and their stakeholders began having deeper and more honest conversations about addressing the longstanding connections between racism and the child welfare system.” It was in that context that the Pritzker Center invited Jessica Pryce to present a three-part series on how to eliminate bias in the child welfare system, which included a discussion of blind removal. The following September, DCFS Director Bobby Cagle expressed interest in developing a blind removals pilot, and DCFS and the Pritzker Center worked to develop a pilot and evaluation plan. But at the same time, Casey Family Programs notified the Center that DCFS also wanted to implement a the “Four Disciplines of Execution,” or 4DX, a framework bills itself as a “simple, repeatable formula for executing your most important priorities.” The Pritzker Center evaluators report that they warned against implementing both programs simultaneously in the same offices, as it would be impossible to identify the source of any change that occurred.

In February 2021, DCFS submitted a letter to the Doris Duke Foundation in support of a grant to the Pritzker Center to evaluate blind removal. But in March, 2021, DCFS withdrew its plan to pilot blind removal. Meanwhile, 4DX was implemented in regional offices throughout Los Angeles County with a goal of “safely reducing entries” into foster care for Black children by 10 percent. The Pritzker Center met with DCFS to discuss an evaluation of 4DX, but no plan was developed. Also in July 2021, the LA County Board of Supervisors passed the motion to pilot blind removal and designated the Pritzker Center as evaluator.

In October 2021, DCFS began meetings with the Pritzker Center to plan the blind removal pilot. It appears that they considered only sites that were in the supervisory district of Holly Mitchell, the Supervisor who had pressed for the pilot. The updates from DCFS to the Board of Supervisors shed more light on the site selection. Only one site was required in the motion that was passed by the Board of Supervisors. In its first update, dated September 13, 2021, Director Bobby Cagle proposed selecting just the West LA office, because it was apparently the only appropriate site that had not implemented 4DX. Cagle argued that it would be a mistake to pilot blind removal at one of the other sites because the “core of the 4DX work is rooted in authentically seeing and addressing families through a cultural lens.” Shifting to a methodology that negates this approach, Cagle argued, would be “contradictory to helping staff make the adaptive change toward leaning into a family’s natural strengths, focusing on natural supports, and activating community partners as resources to mitigate Black/African American children from entering care.” But in the second progress report, dated May 2, 2022, Compton-Carson was listed as a second pilot site with no explanation. And in the third progress report, dated August 1, 2022, the new DCFS Director, Brandon Nichols, explained that Compton-Carson was added because it had already implemented 4DX, unlike the other sites that were still in the implementation phase.

It is understandable that a second site was added, as the numbers in West LA are so small, even though Cagle inexplicably reported to the the Supervisors that the two offices “have the additional benefit of serving a large enough population of Black/African American children to allow for sufficient sample sizes during the pilot phase.” We can now understand the lack of a comparison site, since it appears that no sites were available within the supervisory district that had not implemented 4DX or other interventions, and the small number of available sites may not have included one that was comparable to West LA. But it is clear that not only did the implementation of 4DX possibly contaminate the results of the pilot, but the various programs got into each other’s way in Compton-Carson. That office implemented not only blind removals and 4DX but also another program called Eliminating Racial Disparities and Disproportionality (ERDD), which provided “roundtables, cultural brokers, and father involvement.” The authors of the study report that because of the blind removal process, Black children could not be referred to ERDD until they had been removed, while it was normally used to prevent removals.

Reading between the lines, it appears that DCFS and the Pritzker Center were saddled with the blind removal pilot at a time when they had already lost interest in that program. Both the Center in its evaluation and Cagle in his updates made clear that they saw a conflict between the idea of blind removals and the color-conscious vision behind the other approaches they were implementing, and they both favored the latter. The Pritzker authors wrote, “Colorblind approaches are widely considered harmful to Black people and people of color because they seek to negate race and all the experiences that come with being a racial minority in this country.”

The Pritzker Center also had methodological reasons to avoid blind removals: they had already warned about the problems of evaluating any program when another program is implemented at the same time. Even though the 4DX implementation was complete, one might assume that lasting effects would be expected–and hoped for. It does not appear that anyone had looked closely at Pryce’s data; Cagle was still saying on August 1, 2022, that “[g]iven the successful research findings from New York’s study, …DCFS is excited about piloting Blind Removals in the hopes of achieving similar outcomes…”

To add insult to injury, the county was forced to pay for its no-longer-wanted blind removals pilot. In a classic example of an unfunded mandate, the Board of Supervisors directed DCFS to find $150,000 to fund the blind removals pilot, a directive with which DCFS duly complied. And the Pritzker Center had no choice but to accept the funds that DCFS was directed to provide. Despite their clear negative feelings, the authors tried to justify their work on blind removal, arguing post facto that “the blind removal pilot was viewed as an opportunity to assess the attitudes and perspectives of DCFS staff and social workers toward race, racism and racial bias. Thus, whereas the strategy itself involved a color-blind protocol, the day-to-day experience of blind removal involved significant and insightful discussion about the role of race in child removal.” But it seems unlikely that the pilot was viewed beforehand as an opportunity to assess staff attitudes. And the “insightful discussions” are hard to reconcile with the survey results showing no change in how most workers did their jobs or talked about race and ethnicity.

In the end, the authors tried to reconcile their original goal with the final product by saying the report “articulates a vision that thoroughly documents the pilot, but necessarily urges readers and stakeholders to imagine a color-conscious future for Black families that goes well beyond blind removal.” Bizarrely, though, they insisted that for some jurisdictions, “blind removal may be a worthwhile effort given the possibilities it holds when implemented with proper support and the insights it can afford concerning race and racism within the agency.”

Blinded by ideology

In addition to the difficulties caused by the adoption of multiple interventions at the same time, the blind removal evaluation was flawed from the beginning by the failure to question basic assumptions behind the concept. In their explanation of the idea, the report authors state that “It is hypothesized that racial disproportionality will be reduced because the investigative team’s implicit biases will be mitigated by the case reviewers’ input on the case’s merits for removal.” The missing piece is the assumption that such implicit biases are a major cause of disproportionate removals of Black children. The agency and the evaluators completely ignored the research that suggests that the bias (if any) is probably in the other direction. Most recently, a paper by Brett Drake and a star-studded group of researchers*** shows that once reported to CPS, Black children were slightly more likely to have been substantiated as victims of neglect and placed in foster care than White children until 2011 and somewhat less likely to be substantiated or placed thereafter. In the last few years before the Covid-19 pandemic, they calculated that Black children were about 80 percent as likely to be substantiated and placed as white children, whether or not demographic factors were held constant. Perhaps the increasing concern about disproportionate removals of Black children has been causing social workers and supervisors to be biased in the opposite direction.

Even if the evaluators did not learn from prior research, they could have tried to assess whether investigator bias was actually a cause of disproportionate removal of Black children. They could have collected data at both sites about the proportion of decisions that were overturned by the reviewers, the reason for these reversals, and whether being blind to race had any impact at all. Perhaps they would have learned something about what happens when race and ethnicity are hidden, or perhaps they would have found that hiding these characteristics is impossible. But the authors of the evaluation were apparently too blinded by ideology to even consider the possibility that past rather than current racism is behind current disproportionalities in child welfare. Of course it is not just the researchers, but also the leadership of DCFS, that labored under the assumption that the biases of social workers determine the disproportionality in child removals.

The assumption that disproportional representation in child removals reflects racism in the child welfare system does more damage than simply leading to the adoption of ineffective programs. If the assumption is wrong, as the research suggests, then Black children’s overrepresentation in reporting, substantiations, and removals reflects their real need for protection. And if a child welfare system finds a method that is actually effective in reducing Black children’s representation in child welfare systems, then we are effectively lowering our standards for safely parenting Black children. And that is obviously fine with the authors, who made no bones about their feeling that concerns about child safety unnecessarily interfered with implementation of the pilot. As they wrote:

In general, the West LA staff strongly believed that the slightest concern about safety trumped involvement in the pilot. Though well intentioned, these safety concerns may be informed by bias and thus impede the widespread application of blind removal to families in the West LA office. Across child welfare systems, safety concerns are often prioritized over diverting families from system involvement.

Beyond Blind Removal, page 27.

It is obvious that the authors believe child safety should take a back seat to diverting Black families from child welfare involvement. And there is reason to fear that this happened in Compton-Carson, where removals of Black children fell sharply between Quarter 2 of 2022 and and the same quarter of 2023. Perhaps the LA County has found an intervention that is effective in reducing the removals of Black children absolutely and relative to other groups. Cagle reported that 4DX produced a 47 percent decrease in Black children removed within seven months. That is a pretty radical change–a change that may have severe costs to Black children.

The blind removal report tells a strange and complicated story. It is the story of a pilot program that was apparently imposed by a politicians on a child welfare agency and an evaluator that had moved beyond that program in search of more color-conscious approaches. It is a story of an agency that adopted these preferred approaches simultaneously with blind removal, making it impossible to evaluate any of the interventions. It is the story of researchers and an agency who never stopped to examine the data on blind removals provided in a TED Talk, and who never stopped to think about the assumptions behind this approach. It is the story of an attempt to make it appear that this pilot was anything other than a waste of time and money.

Many thanks to Brett Drake, who made me aware of this report and who shared his thoughts about it.

Notes

*They report that Compton-Carson had higher fidelity to the model because more children’s cases (195) were referred to blind removal than the number of children for whom court petitions were filed (146). But this is confusing compared to the description for West LA, which speaks of the proportion of petitioned children who were subject to blind removal. When I requested clarification from the researchers, they simply restated the language from the report.

**In his first update to the Board of Supervisors, Cagle reported that the offices participating in 4DX had experienced a 47 percent reduction in Black children removed between January and August of 2021. The Compton-Carson data shown above documents part of that drop in the Compton-Carson office.

***Brett Drake et al., “Racial/Ethnic Differences in Child Protective Services Reporting, Substantiation, and Placement, With Comparison to Non-CPS Risks and Outcomes: 2005-2019. Child Maltreatment 2023, Vol 0(0) 1-17.