by Marie Cohen

This blog has often focused on the uncritical use of flawed research to support desired conclusions. A good example of this has now become available. The authors of a new study conclude that decreasing rates of entry into foster care are not associated with changes in mortality from child abuse and neglect. Advocates of continuing reductions in foster care or its total abolition have lost no time in sharing the results, undaunted by what should have been obvious to any knowledgeable reader. The study is too flawed by the nature of its data on child maltreatment fatalities to make any conclusions about the presence or absence of a connection between foster care reductions and changes to child maltreatment mortality.

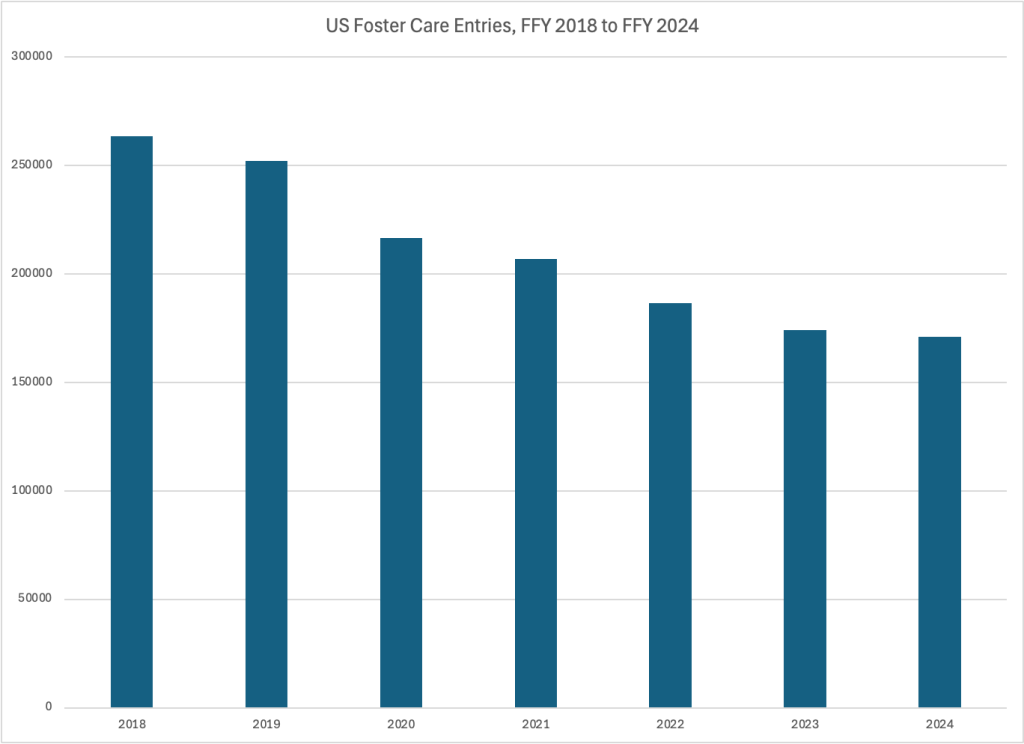

The number of children entering foster care in the United States has fallen from 252,198 in Federal Fiscal Year (FFY) 2019 to 170,955 in FFY 2024. As computed by Frank Edwards, Kelley Fong, and Robert Apel in their new paper, foster care entry rates have decreased from 3.49 to 2.47 entries per 1000 children between 2018 and 2023, a decrease of about 29 percent. This large drop in foster care entries was in large part the result of a growing bipartisan consensus on the federal level and in red and blue states around the need to reduce or entirely terminate the use of foster care to protect children from continuing abuse or neglect.

Some child advocates and media outlets around the country have argued that the reductions in the use of foster care have gone too far. The Seattle Times Editorial Board recently told readers to “Stop dodging and face facts: More kids are dying on DCYF’s watch,” citing a 35% drop in dependency petitions to take kids into foster care since 2021 along with a 67 percent increase in child deaths and near-deaths between 2020 and 2024. A series from Texas Public Radio called When Home is the Danger suggests that a 40 percent reduction in removals of children to foster care, at the same time as in-home services were being curtailed, has resulted in more children dying as a consequence of abuse or neglect. Child advocates across the country have expressed similar fears, but there has been no good data to support or refute this claim.

Edwards, Fong and Apel say their new study shows these fears are baseless. They report that they “found no evidence of a negative association between foster care entries and child maltreatment fatalities at the population level.” They came to this conclusion by estimating the association between child maltreatment mortality rates and foster care entry rates at the state level, using state administrative data from Federal Fiscal Years 2010 to 2023. Even after controlling for variations in population disadvantage, other state features, and national temporal effects they found no association between foster care entry rates and child maltreatment mortality rates.

Advocates of continuing reductions in, or outright elimination of, foster care have been circulating the article widely, using it to counter any claim that excessive foster care reductions may be leading to child fatalities. But a cursory review shows that the study is fatally flawed and would not have been published had the peer reviewers been familiar with the sources of the data used. Four of the leading academic researchers in the field have already posted comments pointing to issues with the data and the model. These comments are summarized and explained below, along with examples from my research on child maltreatment fatality data.

Flawed Data

The Edwards study uses child maltreatment fatality data from the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) to represent child maltreatment deaths. These numbers appear in the annual Child Maltreatment reports released by the Children’s Bureau. In a report called A Jumble of Standards: How State and Federal Authorities Have Underestimated Child Maltreatment Fatalities, I summarized the results of my review of ten years of federal Child Maltreatment reports, including all the state commentaries provided in each report. My work points to multiple reasons that these numbers reported by the states should never be used in such a study.

Screening Policies

The number of child maltreatment fatalities a state will find depends first on which deaths it accepts for investigation and which ones it screens out. And when these change, the number of fatalities found will probably change. For example, some states or counties historically screened out cases where there were no other children in the home,1 because investigations were not considered necessary to protect the other children in the home. West Virginia began investigating cases with no surviving children in the home in FFY 2016. Alaska changed its policy in 2023 so that it will now investigate cases where there are no surviving children in the home, which will affect future counts. We do not know how many states may have made this or similar changes over the span covered by the Edwards paper.

Texas changed its screening policy as of September 2022 so that “reports that involve a child fatality but include no explicit concern for abuse and neglect” are not investigated until the reporter or first responders are interviewed to find out if they had any concerns for abuse or neglect. Only if they had such concerns is the report investigated. DFPS reported that as a result, the number of child fatalities it investigated decreased from 997 in FY2022 to 690 in FY2023 (a 31 percent decrease) due to this new screening policy. And the number of child maltreatment fatalities found fell from 182 to 164.

Changed screening policies can also lead to an increase in reported child maltreatment fatalities. In 2022, Maryland implemented a policy that requires local agencies to screen in sleep-related fatalities, which often involve parental substance abuse. In its commentary, the agency indicated that this was the reason it reported an increase in child deaths from 68 in FFY 2022 to 83 in FFY 2023.

Definitions

NCANDS defines a child maltreatment fatality as “the death of a child as a result of abuse or neglect because either: (a) an injury resulting from child abuse or neglect was the cause of death; or (b) abuse and/or neglect were contributing factors to the cause of death.” So a state’s definition of a maltreatment fatality depends on its definition of child abuse and neglect. And if that definition changes over time, that will affect the trend in child maltreatment fatalities reported. For example, Texas changed its definition of child neglect in 2021 to require “blatant disregard” for the consequences of an act or failure to act. Texas reported a drop of in the number of child maltreatment fatalities from 255 in 2020 to 205 in 2021 to 176 in 2022. The state has attributed that decline in reported neglect deaths to the 2021 law.

A similar decrease in reported child fatalities occurred in Illinois, where “blatant disregard” was already included in the definition of neglect but the requirement was enforced through a new administrative review process for sleep-related deaths. A senior administrator reviews the investigation to ensure that death included evidence of “blatant disregard.” In its 2023 commentary, Illinois links this new policy with a decrease of 24.6 percent in reported child fatalities in FFY 2023.

Data Sources

Experts widely agree that NCANDS underestimates the total number of child maltreatment fatalities, as Edwards et al. acknowledge. One reason is that many states do not use all of the available sources for possible child maltreatment fatalities, which include reports to child protective services, state vital statistics departments, state child death review teams, law enforcement agencies, and medical examiners or coroners. Some states have recently been broadening the sources of data they use, and such changes may have resulted in an increase in reported fatalities. For example, North Carolina originally reported only deaths that the chief medical examiner classified as “homicide” by a parent or caregiver as child maltreatment fatalities. (This does not jibe with the NCANDS definition of child maltreatment fatality, but there is no consequence applied to states who do not use it.) After the agency began to include child deaths that were substantiated as maltreatment by CPS, as well as increasing their collaboration with vital statistics and criminal justice agencies to identify maltreatment deaths, North Carolina’s reported child fatalities increased from 64 in FFY2018 to 111 in FFY2019 (a 73 percent increase).

Historically, Mississippi also reported only deaths that the chief medical examiner had classified as homicide by a parent or caregiver but in 2007 began including fatalities substantiated by CPS as due to maltreatment. In FFY 2014, Mississippi developed a Special Investigations Unit to investigate all reports of child fatality that meet criteria for investigation. Mississippi reported that the having dedicated, specialized investigators resulted in a higher count of maltreatment fatalities in that year and thereafter.2 The state also reported that public awareness campaigns to prevent deaths caused by unsafe sleep and children left in hot cars led to an increase in reporting of such fatalities, also contributing to an increase in reported deaths. The number of child maltreatment fatalities reported by Mississippi increased from 17 in FFY 2010 to 76 in FFY 2023.

Reporting Errors

In 2025, a reporter at the Baltimore Banner noticed that Maryland was reporting an alarming rate of child fatalities. With a reported 83 children dying of abuse or neglect in FFY 2023, Maryland had one of the worst child maltreatment fatality rates in the nation. Taken by surprise, state Department of Human Services officials soon realized that they had been reporting incorrect numbers for the past five years. Instead of reporting the deaths for which maltreatment was confirmed, they had been reporting all child deaths that had been investigated for maltreatment. The department now believes that there were 173 child maltreatment fatalities, not the 285 reported, between FFY’s 2020 and 2023. We do not know how many other states have been reporting erroneous numbers, given the little attention that these reports usually receive.

Time Lags

A key flaw of Edwards et al.’s analysis is the assumption that child maltreatment fatalities reported for a specific year reflect the deaths that occurred in that year. That is far from being the case. As the Children’s Bureau explained in Child Maltreatment 2023, “The child fatality count in this report reflects the federal fiscal year (FFY) in which the deaths are determined as due to maltreatment. The year in which a determination is made may be different from the year in which the child died.”3 There is similar language in reports from the previous years. States have explained in their commentaries that the actual dates the children died may have occurred as much as seven years before the year they were reported. As Sarah Font of Washington University and Emily Putnam-Hornstein of the University of North Carolina explain in their comment (posted below the article), “the Edwards et al. analysis largely models whether state foster care entry rates predict past [child maltreatment fatalities] — a nonsensical question with no bearing on whether foster care is a protective intervention. Indeed, if states respond to rising [child maltreatment fatalities] by placing more high-risk children in foster care, one would expect higher past [child maltreatment fatality] rates to be associated with higher current foster care entry rates.”

Even if the fatalities did occur in the same year as they were reported, it would not make sense to expect an increase in deaths only in the same year as a decrease in foster care, Brett Drake of Washington University raises this concern in his comment. Any maltreatment fatality resulting from a failure to remove a child will not necessarily occur in the same year. A foster care removal may save a child’s life in a subsequent year. Many of the most horrific child fatality cases involve child fatalities that could have been prevented by removal in prior years. In some of these cases, the child suffered through years of abuse or neglect before dying. But as Font and Putnam-Hornstein point out, the Edwards model attempts to correlate removal rates with past child maltreatment fatalities. And there is no way that makes sense.

Other flaws in the model

Font and Putnam-Hornstein, as well as Richard Barth of the University of Maryland, draw attention to another problem. Children under age five account for 82 percent of reported child maltreatment fatalities but less than half of foster care entries. But proportional decreases in foster care entries were largest among older children: there was a 49 percent reduction in entries of 17-year-olds versus an 18 percent reduction in infant entries. It might have been more sensible to focus on younger children only, though fixing this problem would not address all the other problems with the analysis.

Barth suggests another problem with the model. Placing a child in foster care may prevent that child dying from other causes, not just maltreatment. And indeed, we have learned that maltreatment is correlated with deaths from all causes, not just from child maltreatment. Research shows that children who have been reported for maltreatment are more likely to die of accidents in their first five years, sudden infant deaths and medical causes as infants, and suicide as teenagers. It is also obvious from my personal experience reviewing child fatalities in the District of Columbia that children who die of homicide as teenagers and young adults are likely to have a family history of child abuse and neglect reports. Child maltreatment mortality is only one type of child mortality we should care about.

It is unfortunate that so many child welfare leaders and commentators are so quick to grab hold of any research that supports their point of view without critically examining the methodology and considering whether the findings justify the claims. I hope that the peer reviewers for this study were as unfamiliar with state child maltreatment data as the study authors themselves; otherwise their motives in approving the study are suspect. As Font and Putnam Hornstein put it, “[t]he conclusions of Edwards et al. rest on a mis-specified model and deeply-flawed data; deficiencies unaddressed by the authors’ numerous sensitivity analyses.” These findings have no relevance to the discussion of whether the decline in foster care removals is putting children at risk of dying.

Notes

- Some jurisdictions still do this, including the District of Columbia (as I learned from requesting child fatality information) and some counties in Ohio, as described in Child Maltreatment 2022. ↩︎

- Child Maltreatment 2014, Child Maltreatment 2015, and Child Maltreatment 2016. ↩︎

- Like many statements in the CM reports, this is not exactly true. A few states (including California) do attempt to capture only the deaths that occurred in the reporting year. This involves reporting on only deaths that occurred in the reporting year and then amending the numbers in future years. See A Jumble of Standards. In their eAppendix 1, Edwards, Fong and Appel note that they include the most recent revisions into their estimates. But as I describe in A Jumble of Standards, it appears that only a few states make such revisions. ↩︎

The federal

The federal

On October 29, 2019, the Administration on Children and Families (ACF) announced its first approval of a Title IV-E Prevention Plan to be submitted under the Family First Prevention Services Act (“Family First”). This plan, called

On October 29, 2019, the Administration on Children and Families (ACF) announced its first approval of a Title IV-E Prevention Plan to be submitted under the Family First Prevention Services Act (“Family First”). This plan, called  Passage of the Family First Prevention Services Act as part of the

Passage of the Family First Prevention Services Act as part of the