Lowest number of maltreatment victims in five years, crowed the Administration on Children and Families (ACF), summarizing its annual report, Child Maltreatment 2019. Child welfare newsletter The Imprint eagerly repeated the claim, claiming that the Number of Child Abuse and Neglect Victims Reached Record Low in 2019. The venerable Child Welfare League of America followed suit in its Children’s Monitor saying “Data Shows Decline in Child Abuse in FY2019.” It is only by reading the report that one learns that the decline was not actually in the number of victims of abuse or neglect. Instead, it was a decline in the number of children who were found by Child Protective Services (CPS) to be abused or neglected, which is not the same thing at all.

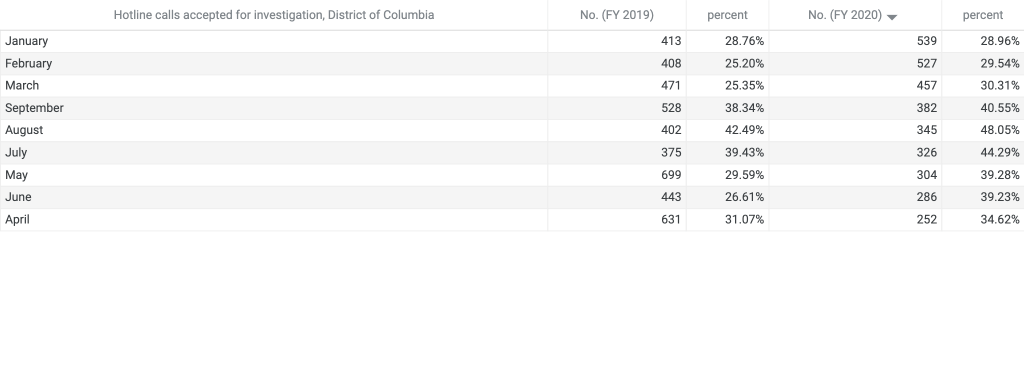

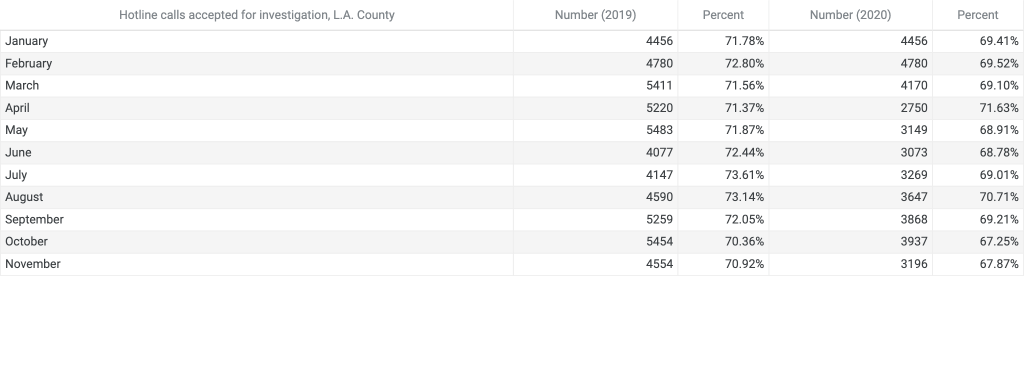

Child Maltreatment, the Children’s Bureau’s annual report on child abuse and neglect, is based on data from the states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico collected through the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS). Child Maltreatment 2019 is based on data from Federal Fiscal Year (FFY) 2019, which ended September 30, 2019. (Note that these data reflect the year before the inception of the coronavirus pandemic.) Displayed below is a summary of four key national rates reported by ACF between 2015 and 2019. The first indicator shown is the referral rate, which describes the number of calls and other communications describing instance of child maltreatment per 1,000 children. Next is the screened-in referrals rate, which includes referrals that are passed on for investigation or alternative response. Once screened in, only some reports are referred for investigation, and the third set of bars represents children who received an investigation per 1,000 children. The fourth group shows the rate of children found to be abused or neglected–or those who received a substantiation. Let us go over these numbers in more detail.

Source: Child Welfare Monitor tabulation of data from Child Maltreatment 2019, available from

https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cb/cm2019.pdf

Total referrals: A referral is a call to the hotline or another communication alleging abuse or neglect. In 2019, agencies received an estimated total of 4.4 million referrals, including about 7.9 million children. The “referral rate” was 59.5 referrals per 1,000 children in FFY 2019. This rate has increased every year since 2015, when it was 52.3 per 1,000 children. It is worth noting that the referral rate differs greatly by state, ranging from 17.1 referrals per 1,000 children in Hawaii to 171.6 per 1,000 children in Vermont, as shown in the report’s state-by-state tables. These differences in referral rates may stem from cultural differences regarding the duty to intervene in other families, differences in publicity for child abuse hotlines and ease of reporting, or temporal factors like a recent highly-publicized recent child abuse death.

Screened-in referrals (reports): A referral can be either “screened in” or screened out because it does not meet agency criteria. In FFY 2019, agencies screened in 2.4 million referrals, or 32.2 referrals per 100,000 children. This was a decrease in the rate of screened-in referrals per 1,000 children after three straight years of increases. This percentage of referrals that were screened in varied greatly by state, ranging from 16 percent in South Dakota to 98.4 percent in Alabama. States reporting a decrease in screened-in referrals gave several reasons, such as a change in how they combine multiple reports and a decision to stop automatically screening in any referral for a child younger than three years old.

Children who received an investigation (child investigation rate): Once a report is screened in, it can receive a traditional investigation or it can be assigned to an alternative track, which is often called “alternative response” or “family assessment response.” (Two-track systems are often labeled as “differential response.”) This rate represents the number of children who received an investigation as opposed to an alternative response. Only an investigation can result in a finding of abuse or neglect; an alternative response generally results in an offer of services. Like the referral rate, the investigation rate increased from 2015 to 2018 and then decreased in 2019. This rate also varies widely between states and over time. Some states eliminated or expanded their differential response programs in 2019, resulting in more or fewer investigations, as described in the report.

Substantiation: A “victim” is defined in NCANDS as a “child for whom the state determined at least one maltreatment was substantiated or indicated; and a disposition of substantiated or indicated was assigned for a child in a report.” The report’s authors refer to the number of such children per 1,000 as the “victimization rate.” But clearly substantiation does not equal actual victimization. The difficulty of making a correct decision on whether maltreatment has occurred is well-documented. Stories of families with repeated reports that are never substantiated or not confirmed until there is a serious injury or even death are legion. So are reports of parents wrongly found to be abusive or neglectful. Therefore, we have chosen to use the term “substantiation rate” instead of ‘victimization rate.” This rate varies greatly by state, from 2.4 per 1,000 children in North Carolina to 20.1 in nearby Kentucky.[1] The national substantiation rate in FFY 2019 was 8.9 per 1,000 children, down from 9.2 per 1,000 in FFY 2019 and FFY 2015. States reported a total of 656,000 (rounded) victims of substantiated child abuse or neglect in FFY 2019–a decline of four percent since 2015.

So does this decline in the number and rate of substantiations really connote a decline in child abuse and neglect? The range in substantiation rates among states argues against this idea. Unless states differ by almost a factor of 10 in the prevalence of child abuse and neglect, these numbers must reflect factors other than the actual prevalence of maltreatment. And indeed the report’s authors acknowledge that “[s]tates have different policies about what is considered child maltreatment, the type of CPS responses (alternative and investigation), and different levels of evidence required to substantiate an abuse allegation, all or some of which may account for variations in victimization rates.” Changes in these policies and practices can account for changes in these rates over time. Moreover, changes in all the earlier stages of reporting, screening, and assignment to investigation or alternative response contribute to changes in the substantiation rate. In 2019, screened-in referrals and investigations per thousand-children both decreased, which clearly contributed to the decrease in the substantiation rate.

It is interesting to note that while referrals increased every year between FFY 2015 and FFY 2019, both screened-in referrals and investigations decreased in FFY 2019. This suggests a general tendency among states to be less aggressive in responding to allegations of maltreatment, perhaps in accord with the prevalent mindset among child welfare leaders nationally and around the country, as discussed below.

Understanding the difference between “victimization” and “substantiation” and the many possible causes of a decrease in this rate reveals the deceptiveness of ACF’s statement that “[n]ew federal child abuse and neglect data shows 2019 had the lowest number of victims who suffered maltreatment in five years.” Lynn Johnson, the HHS assistant secretary for children and families, is quoted in ACF’s press release as saying that “[t]hese new numbers show we are making significant strides in reducing victimization due to maltreatment.” Unless Johnson and the ACF leadership intended to mislead, it appears they are woefully ignorant of the meaning of these numbers.

Most regular leaders of this blog already know why ACF wants to support the narrative of declining child maltreatment. The current trend in child welfare policy, regardless of political party, is to oppose intervention in families. Republicans who oppose government spending and interference in family life have made common cause with Democrats who think they are reducing racial disparities and supporting poor poor families by allowing parents more freedom in how they raise their children, even if it means leaving children unprotected. Members of both parties came together to pass the Family First Act, which encoded this family preservation mindset into federal law.

Child Welfare Monitor has pointed out many other instances where ACF or by other members of the child welfare establishment in the interests of supporting the family preservation mindset. For example, we wrote about the Homebuilders program, which was classified by a federally-funded clearinghouse as “well-supported” despite never having been proven effective for keeping families together. In fact, Homebuilders had to be classified as well-supported because it was one of the key programs touted by ACF and others in promoting the Family First Act and other policies promoting family preservation.

So if ACF’s “victimization” data do not in fact tell us what is happening to abuse and neglect rates, what else is available? We call on Congress to pass an overdue re-authorization of the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act and include a fifth National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect. Data for the last study was collected in 2005 and 2006; it is high time for an update which should put an end (at least temporarily) to the misuse of NCANDS data as an indicator of trends in child maltreatment.

President Biden has called for ending a “culture in which facts themselves are manipulated and even manufactured.” We hope that ACF under its new leadership, as well as the rest of the child welfare establishment, will take these words to heart and commit themselves to truth and transparency from now on.

[1]: Pennsylvania has a substantiation rate of 1.8, even lower than that of North Carolina, but in Pennsylvania, many of the actions or inactions categorized as “neglect” are classified as “General Protective Services” and not included in the substantiation rate, making its data not comparable to that of the other states and territories.

[2]: Massachusetts did not provide data on FFY 2019 child maltreatment fatalities.